Before this year ends and the decade of the 2020s gets underway, Apple is poised to unveil a dramatic new architecture for its venerable Macintosh computing platform. Here's why new Apple Silicon hardware is an important step in the future of the Mac.

Why Apple is moving to new silicon

Across the last four decades, Apple has uniquely made a series of radical moves to shift its Mac hardware to entirely new and materially different chip architectures.

No other computing platform has successfully performed such a complex undertaking on a similar scale even once, let alone attempting the three major platform shifts Apple has made on the Mac, from Motorola's 68000 in the 1980s to PowerPC in the 90s and then to Intel x86 in the 2000s.

Each migration involved massive efforts to not only deliver new hardware, but also transform vast software platforms and create new development tools to minimize the transition pain of users and developers. When Apple migrated to PowerPC in the early 90s, other platforms of the day were supposed to complete parallel transitions of their own, including Microsoft's Windows NT, IBM's OS/2, the Commodore Amiga, and many others.

Apple's unique ability to successfully complete the shift to PowerPC was complicated by other firms' failing to do the same, resulting in Apple eventually ending up the only major PowerPC user. The difficulty of that transition and its unexpected result might suggest that in hindsight, it was ultimately a mistake to have attempted such a complex and risky task.

On the other hand, Apple's migration to Intel Macs about a decade later was hailed as a masterful strategic move, enabling Apple to enter new markets and eventually expand its Mac platform dramatically. Yet Apple's move to Intel's chips starting in 2006 was largely enabled by the company's previous PowerPC experience in learning how to execute such a transition.

An Apple Silicon transition that's been underway for a decade

It's useful to examine what benefit there is for Apple to again shift to an all-new chip architecture this year, this time using a custom silicon architecture of its own design rather than buying off-the-shelf chips available to any PC maker.

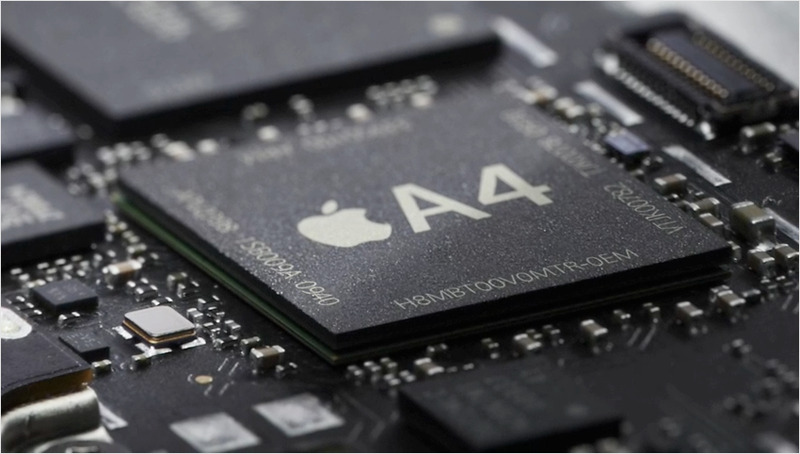

In a variety of ways, the Mac-maker's move to new "Apple Silicon" isn't entirely new. The company has been developing customized "System on a Chip" silicon since 2008, an effort which resulted in the A4 chip that powered iPhone 4, the original iPad, and the first iOS-based Apple TV.

Starting in 2016, Apple began shipping Macs equipped with T1, a custom SoC designed to handle Touch ID security and to provide the System Management Controller features that differentiated Apple's Intel Macs from commodity Intel PCs. Even before the T1, Apple's custom SMC microcontroller managed Macs' power management, battery charging, sleep and hibernation, video display modes, and other features that customized and enhanced the Mac experience.

Since 2017, new Macs have included an even more advanced T2 SoC. This 64-bit chip handles everything from disk encryption to image processing, and enabled features ranging from iPad Sidecar to Hey Siri. The last few years of T2 Macs have effectively been Apple Silicon Macs with an Intel processor providing native x86 software compatibility!

How Macs got hooked on Intel chips

Apple's Intel Macs currently use the same Intel x86 architecture as industry-standard PCs running Windows or Linux. In fact, the Intel chips in today's Macs are inherently what made it so easy for Macs to run Windows software or run an instance of a Linux server.

That commonality and compatibility were originally touted as a major reason for Apple moving to Intel chips back in 2006.

Before that shift, Apple's Macs used PowerPC chips that could boast a number of technical advantages over x86 chips. However, PowerPC increasingly struggled to keep up with the pace of Intel's competitive x86 developments simply due to economic factors.

By 2004, Apple was the only significant vendor left using PowerPC chips. The rest of the desktop computing world had largely converged on x86 chips from Intel, creating vast economies of scale that supported Intel's continued investment in future generations of its x86 chips.

With sales of Macs only growing incrementally and no remaining prospects for expanding the demand for PowerPC chips, the manufacturing partners behind the PowerPC architecture lacked any similarly secure financial backing needed to maintain parity with Intel's relentless pace of ongoing silicon development.

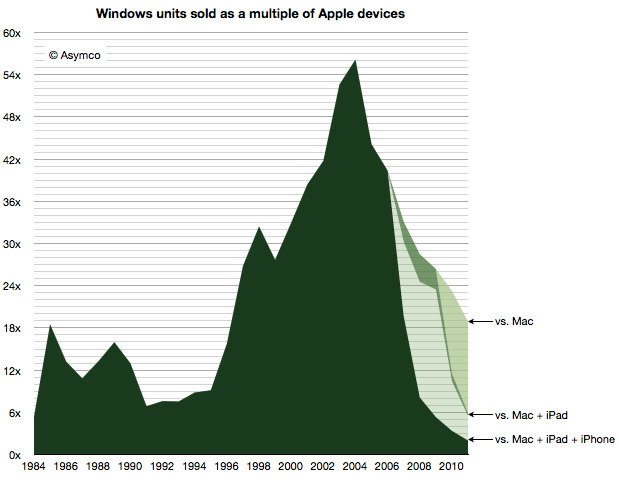

Developing new generations of chips is vastly expensive work that simply couldn't be competitively financed by a single PC maker shipping only around 3.3 million Macs per year. In 2004, Windows PCs were outselling Macs by a factor of 56. PC makers collectively sold 182.5 million units that year, creating a massive gulf between the PowerPC Mac platform and the Intel PC platform.

Apple's jump from PowerPC to Intel erased that chasm and brought Intel's economies of scale to the Mac, making it dramatically easier for Apple to not only keep up with its hardware rivals, but to innovate in other ways that contributed to Macs being more valuable than a bog-standard PC. Apple's macOS itself was a major example of that, adding unique value to Apple's platform in usability, security, and attractiveness.

In 2012, Horace Dediu described for Asymco how Apple turned around Microsoft's dominant position in PCs, detailing how its differentiated Intel Macs rapidly shifted the ratio of Macs to PCs sold.

Apple built a new non-Intel platform larger than the Mac

Another very significant shift began to occur immediately after Steve Jobs first debuted Apple's initial Intel Macs back in 2006. The next year, Apple launched the iPhone, followed by its iOS-based iPad tablet in 2010.

Over the next decade, Apple's new iOS mobile software platform (based on macOS) becomes at least as large and arguably an even more influential software and development platform than Windows, Linux, ChromeOS, or anything else— certainly within the emerging explosion of the mobile market.

Importantly, that new Apple platform didn't need Intel chips. Rapidly expanding iPad sales drove Apple into the role of the world's leading personal computing maker, even as an army of industry marketing groups desperately tried to portray iPad as nothing more than a "media consumption device."

The reality was that iPads and iPhones were commonly replacing the historical roles of PCs while creating new markets for mobile computing that Intel-based PCs couldn't match. It was a case of classic disruption: an innovative new product that could effectively compete against an existing, more complex, and expensive alternative that was "over-serving" the market.

Despite Microsoft's various efforts to make its own "mobile Windows;" Intel's various attempts to drive sales of its mobile x86 chips by Linux and Android makers; and Google's efforts to copy Apple's iPad using Android and also counter it with its own web-based "Chrome" PCs or netbooks, no other company has been able to develop a mobile computing apps platform capable of commercially rivaling Apple's iOS and iPad OS on a similar scale, and with similar commercial results.

Rival mobile platforms supported the economies of scale that benefitted iOS

In fact, no one else has been able to achieve Apple's success because nobody actually copied what Apple was doing. ChromeOS came closest: like Intel Macs, it launched a unique OS on relatively standard hardware.

Google just failed to gain any adoption for ChromeOS outside of U.S. schools looking for very cheap hardware.

Android licensees have collectively shipped lots of smartphones, but the value of the Android platform has splintered between app stores and hardware platforms. Rather than driving economies of scale that Apple couldn't match, the commonality of Android licensees has largely just supported a more important industry-standard: ARM architecture hardware.

Because Apple was also using ARM chips in its iOS devices, it benefitted tremendously from the industry's common use of the ARM architecture, including all the collective efforts poured into ARM silicon development and ARM architecture software tools, compilers, and other efforts.

So while Macs were leveraging Intel's PC commonality to advance the unique value in macOS over Windows or Linux, Apple's mobile device sales were leveraging the ARM architecture to support iOS and iPadOS as superior alternatives to Android.

But there was also a difference: while Intel's desktop x86 represented a proprietary processor platform, the mobile ARM architecture was a technology Apple could license and independently develop on its own, adding unique value on the silicon level in the same way it had been doing in software with macOS, iOS and iPadOS.

Embrace, extend, extinguish

By moving future generations of its Macs to its own uniquely enhanced silicon, Apple is again able to benefit from both common economies of scale and proprietary advancements that add unique value. It's noteworthy that other competitors in the PC and mobile space have tried but failed to similarly do this.

Both Samsung and LG have attempted to acquire and develop their own unique software development platforms with Tizen and webOS. Yet outside of the smaller markets for smart TVs and watches, Android has effectively blocked their ability to drive volume sales of differentiated software on standard hardware, whether in phones or tablets or notebooks.

Huawei has similarly claimed that it is close to introducing its own internal OS platform out of necessity after the U.S. blocked it from using Google's Android. But this has been merely disruptive to Huawei's sales, because existing Android buyers don't want a non-standard, non-compatible Android alternative.

Android was supposed to unite the industry against Apple. Instead, it has locked its licensees into a dependence upon Google and its policies, while effectively preventing those licensees from freely innovating on their own with their own software platforms.

In the other direction, Microsoft has made multiple attempts to shift Windows PCs and mobile devices from Intel to ARM, leveraging the mobile advantages of the ARM architecture. But Microsoft lacks Apple's ability to decisively shift its entire platform to a new chip architecture because the majority of Microsoft's Windows platform is delivered by PC licensees.

The minority of Windows-on-ARM devices that Microsoft and its partners ship simply splinters the Windows platform without offering significant added value. Unlike Apple, Microsoft also has no silicon expertise of its own, simply leaving it newly dependent on Qualcomm rather than Intel, and straddling both chip architectures the same way that Google's support for both ARM and Intel in Android was a splintering liability rather than a real advantage.

Apple Silicon gives Macs a new platform advantage

In shifting from Intel x86 chips to its own Apple Silicon SoCs, Macs will lose some of the hardware compatibility they gained back in 2006. However, two things have changed since then.

First, the need to run Windows has fallen dramatically for many people for whom it was once very important. Secondly, Microsoft itself has developed the native ability to run Windows on ARM.

In parallel, Apple Silicon Macs will gain the ability to natively run ARM software developed for iOS. That not only means it will be a bit easier to develop for iOS on Macs and to migrate iOS apps to run on Macs, but also that it will be easier for both Apple and third-party developers to develop software tools and specialized code that uses not just ARM Architecture CPUs, but also the other silicon engines Apple has developed, including its custom Apple GPU, the Neural Engine, and features like its AMX machine learning accelerators.

For most users, these new advantages from Apple Silicon will be far more valuable than running the x86 version of Windows natively.

Note also that all of these custom silicon processor engines, each tuned to specific types of operations, are only a few years old. Driven by continued sales of iPhones, iPad, and Apple Silicon Macs, future development of Apple Silicon SoCs can adapt to handle specialized new functions that evolve in the near future.

By using its own silicon designs everywhere, Apple can not only enhance the Mac but also more rapidly bring advanced new technologies to other new products ranging from new types of wearables to home devices.

Rather than being stuck with the basic Intel x86 architecture that is optimized to deliver a classic PC experience, Apple can enhance its Apple Silicon Macs to deliver notebook and desktop machines that share more of its own vision for devices that don't just calculate but blur the line between hardware and software in the model of Apple Watch, and seamlessly integrate with other devices in the model of Continuity.

T2 Apple Silicon

Apple has already pursued these goals by integrating large parts of its existing A-series chips into recent Macs by way of the T2, which brought Apple's custom codecs, storage controllers, and security features such as the Secure Enclave to Macs.

In going one step further to replace Intel's CPU, its integrated GPU, and other features currently handled by an x86 chip and the supporting hardware developed around Intel's x86 architecture, Apple can radically take future Macs in a new direction that will leave behind standard PCs the same way that iPad has left simpler Android tablets in the dust, or the way iPhone silicon has rapidly advanced beyond what is even available in an Android phone.

Custom T2 Apple Silicon has already brought differentiating features to Intel Macs, including Touch ID, SideCar, Touch Bar and Hey Siri

Custom T2 Apple Silicon has already brought differentiating features to Intel Macs, including Touch ID, SideCar, Touch Bar and Hey SiriOver the past ten years, Macs have increasingly been held back by Intel's x86 architecture more than they have benefitted from its economies of scale. It's now the perfect time to shift mobile Macs to the much more power-efficient, graphically powerful, and broadly sophisticated imaging and machine learning silicon that shares economies of scale with Apple's own iOS hardware.

Additionally, Apple will gain another major benefit: leveraging the advanced 5nm silicon manufacturing technology of TSMC that is far ahead of Intel's current 10nm chip manufacturing capacity in its tenth generation Ice Lake x86 chips.

This is also a big loss for Intel, as Apple represents one of its most valuable and technologically demanding clients. With Microsoft and other PC makers also shifting some of their production to various alternative chip makers, the Intel x86 platform will suffer a major weakening of its economies of scale, something that will also detriment every PC maker relying on Intel to help them keep parity with Apple.

Recall that it was Intel that drove industry-wide efforts to get PC makers to deliver ultralight notebooks that could compete with Apple's MacBook Air.

With Intel increasing unable to help PC competitors copy Apple's work, we're likely to see Macs peel ahead of commodity PCs at a pace closer to iPads advancing beyond other tablets, or Apple Watch leaving behind other smartwatches, or iPhones advancing while Android phones scale back their ambitions to instead reach lower price points.

That will be an important development because PCs under the control of Intel have not previously advanced as fast as mobile devices have. It's also a development that could spur other companies to try new approaches rather than just cranking out more generic PC boxes wrapped around an Intel platform and running a Microsoft OS.

If they are unable to compete, we're likely to see a major new bloom in Mac sales that brings more advanced, connected, and broadly powerful computing to creative users, to businesses, to education, and elsewhere, driving similar advancements in desktop computing as we've already seen in phones and tablets.

And if anyone else is able to compete, we'll see even broader technical advancements driving the state of the art even faster.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger-xl.jpg)

-m.jpg)

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

-m.jpg)

122 Comments

The title is about the future, the content about the past.

Here’s a thought about the future — I wonder if “desktop AI/ML” will define the Mac of the 2020s the way desktop publishing did in the 80s.

This article paints a too rosy picture of the transition. The fact of the matter is that moving away from x86 will end Mac’s “best of both worlds” status. That means no more running Windows software.

I’d rather keep the genuine Mac experience in software as opposed to the lazy iOS ports we will now largely be stuck with.

What this story omits is that, while the Mac line has been a niche product in the industry, it is now a niche product within Apple's spectrum of devices and services.