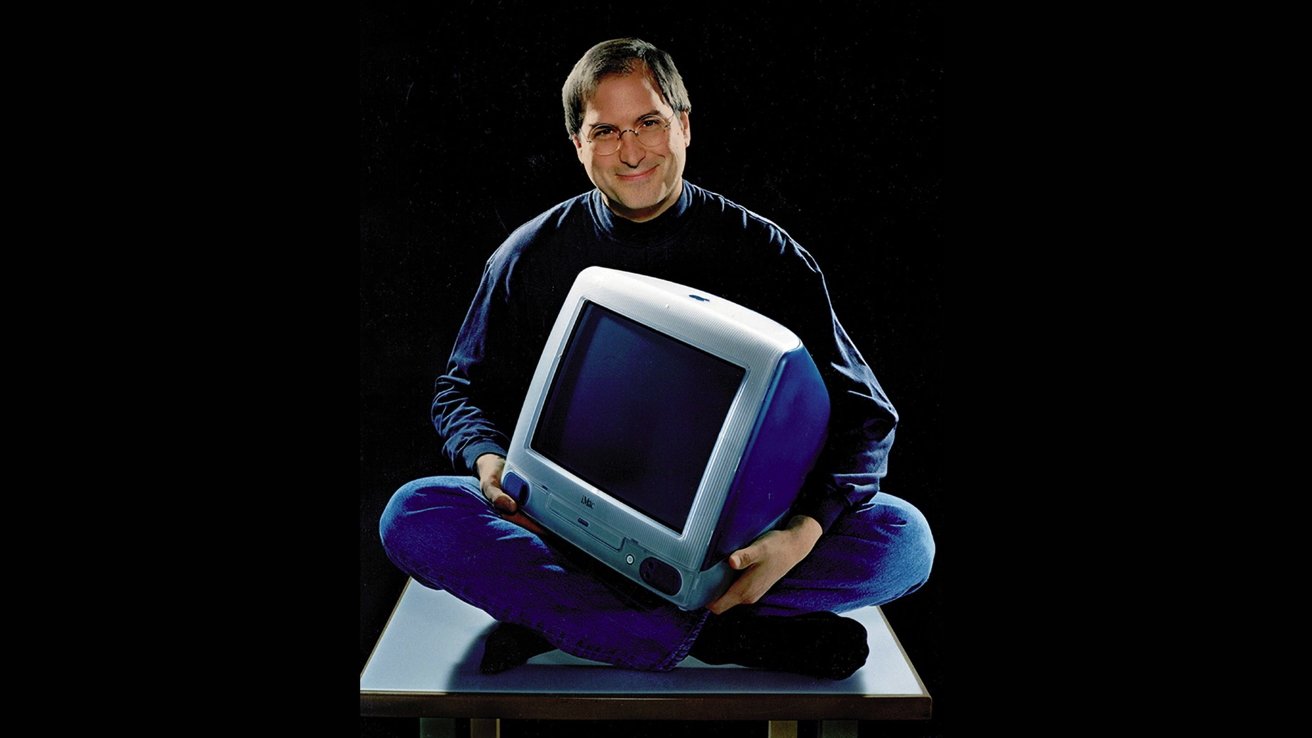

How Steve Jobs saved Apple with the iMac 26 years ago

Last updated

On May 6, 1998, Steve Jobs announced the iMac, and we wouldn't now have the iPhone, the Apple Store, or even Apple itself, if it hadn't been such a success.

If there's ever any doubt that the iMac is a phenomenal success, just try to think of any other computer — any other device — that is still being sold a quarter of a century after it was launched. The iMac of 2023 may be vastly different to the original one announced in 1998, but it's not just that it has kept the name.

Today's iMac is this slim, sleek design and 1998's was fat and bulbous, but they are recognizably the same at heart. The iMac has always been an all-in-one computer, where a single unit houses the display and the actual computer part.

All in One

In the 1990s, existing computer users and the trade press all saw that this meant owners couldn't mix and match different screens or other peripherals. They saw that you got what you got, and if you wanted something else, that was your problem.

"But the iMac (pronounced EYE-Mac — the ''i'' stands for Internet) also departs from computer industry standards in other ways, and customers will have to decide whether different means better," wrote the New York Times in 1998. "The drawback of such a design is that people are locked into using the iMac's 15-inch screen... [but] the iMac screen is one of the best 15-inch displays available."

"A few customers may be able to work effectively without some way to transport data physically, by backing up files to a network server or to the Internet," continued the publication, "but most of the consumers Apple is trying to appeal to live in a world where floppy disks are important."

"After ignoring the home market for a couple of years, the Mac is back with a vengeance," wrote the Los Angeles Times in May 1998. "The iMac boasts ample power, great features, competitive pricing and a radically new look — curvy, translucent, blue and white."

"To my eye, it's far from beautiful, but what matters is this: The iMac is so different from the norm that people will pay attention," continued the paper. "And if Apple needs anything these days, it's attention as an innovator."

The Los Angeles Times generally praised the iMac, but still added "my guess is that Apple is wrong about home users — most will still want a floppy (or zip drive) and will have to buy an add-on."

What Apple saw that we now know the entire rest of the computer industry missed was that all of this was exactly the point. Just as he had with the Macintosh in the 1980s, Steve Jobs wanted the iMac to be an appliance — a single device you used rather than customized.

In the 1990s, he got what he wanted and it worked in every possible way. From the iMac onwards, Apple focused on consumers, and it's like it's the only firm that didn't see that as a bad thing.

"We have been working hard on fashion, which is very important in the consumer market," Steve Jobs told financial writer Lou Dobbs on CNN Money during the week the iMac launched.

Bill Gates knows best

It's not clear now exactly when Bill Gates mocked the iMac, but some time around 2000, he famously dissed it and Apple.

"The one thing Apple's providing now is leadership in colors," he said. "It won't take long for us to catch up with that, I don't think."

Gates was referring to how the iMac came in a small rainbow of different colors, but Apple was far from ignoring technology in favor of a paint brush. Jobs had no qualms talking about fashion and consumers, but he was at least equally firm about specifications.

"This one [the iMac] is incredibly sweet," he said in that Dobbs interview. "This $1,299 product is faster than the fastest Pentium II you can buy. The market's never had a consumer computer this powerful and cool-looking."

Jobs was always the sharp businessman and he told Dobbs that of its 22 million customers at the time, 10 million were consumers. Not only did that mean Apple should pay attention to who was buying its devices, Jobs said it meant that the company had a chance to get those consumers to buy more Macs.

"Those users haven't been upgraded because of viability concerns about Apple, which I think we've overcome," he Jobs. "And we haven't given them a good product in a long time."

It didn't always look this way

Today the iMac is a staple of countless universities, offices, and homes, and throughout even its earliest days, Steve Jobs sounded like that success was obvious. In reality, the choice to even make a new Mac was a risk, and to go so far away from tested successes was nothing short of a gamble.

It was also a gamble that Apple could not survive losing.

The iMac project was begun pretty much as soon as Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, but his job was not to create a new product. It was ultimately to save the company which Jobs later revealed was within 90 days of going bankrupt.

When a company is failing, there's obviously a drive to cut costs, and there can be a determination to show there's still life left in the firm. A way to do that is indeed to launch a new product and Apple did that — with the Twentieth Anniversary Mac.

It was bold, its designers included Jony Ive, but it was late when it was announced, and it was later still when it shipped. The machine missed Apple's 20th anniversary by over a year, and then it was a flop anyway.

As a business, Apple was on its last breath, and the one thing it perhaps still had going for it was that it could design a good computer. The Twentieth Anniversary Mac seemed to show that either Apple had lost that knack, or maybe that design didn't matter any more.

To get a true feel for how bad things were, picture Apple CEO Gil Amelio coming on stage at Macworld 1997 and making what Michael Markman, a former director of advertising and creative services at Apple, persuasively describes as The Worst Apple Keynote Ever.

That was what Apple was presenting to its loyal user base, and to the world. Apple was saying that it had nothing, no products it cared about, nothing.

Apple had just an increasing amount of money being lost, and the certainty that layoffs were coming.

But then it also got Steve Jobs, and it got NeXT. Jobs came back to Apple at its lowest point, and he was ruthless at cutting anything he didn't think was right. With behind the scenes politics, that even included forcing Gil Amelio out.

Jobs's cuts very publicly included the whole Newton MessagePad line. Less publicly noticeable were cuts like ending Apple's OpenDoc software plan.

In what was called a "fireside chat" at WWDC 2007, Jobs talked specifically about cutting OpenDoc, and was blunt with developers about what Apple was going to do. He was critical of Apple's recent past, but the frankness of what he saw working and not working was refreshing.

More than two decades on, we are living in the future Jobs predicted in that chat. But every specific hardware or software he mentioned is long gone — and yet the whole video is still utterly compelling.

It's quite a technical video in that its a film of Jobs talking with developers, but even here Jobs was looking to how Apple could make better computers for consumers. He gave as an example, how he hoped Apple could make networking be as simple for users as the Mac had made using a computer.

"That's one of the things where I think there's a giant hole [in the market for Apple to fill]," he said. "And I can't communicate to you how awesome this is unless you use it."

The iMac was Apple's way of trying to communicate this and all of Jobs's ambitions. It didn't just include the option for networking, it forced people to network by removing the floppy disk.

"Apple contends that the 1.44-megabyte, 3.5-inch disk drive is a thing of the past," said the New York Times, "and that putting one in the iMac would have made it last year's machine instead of next year's."

"The iMac is Jobs' first real technology statement as interim CEO," continued the Los Angeles Times. "It's classic Steve Jobs— a gamble. But it looks like a good bet to me."

Apple was nervous

Even the critics who thought Apple was dumb over the floppy disk, were at the very least covering Apple. Most had positive things to say, too, and of course Steve Jobs exuded total certainty about the iMac's strengths — and total confidence about its success.

Then, too, we are looking back at the iMac after more than two decades of it being a hit.

And there were those 1997 TV ads with Jeff Goldblum, talking about how obvious and easy the iMac is.

So it's hard to imagine, and a little hard to be sure, but there are signs that Apple had doubts. And they're all in Apple's advertising.

The first mention of the iMac on Apple's online site tries wincingly to be hip and cool. "It's a good thing there's no law against a company having a monopoly of good ideas," it said. "Otherwise Apple would be in deep yogurt for the ideas that Steve Jobs shared with the crowd at Apple's Flint Center auditorium Tuesday, May 6."

There are then there was an attempt to slot the iMac into Apple's lineup that at this time went Power Macintosh G3, PowerBook G3, and iMac. Which were listed repeatedly as "Pro, Go, Whoa."

The strapline for that iMac "Whoa" spot on the website ran, "It's okay, you don't have to say anything."

What Apple kept saying once the iMac was shipping in August 1998, and what Apple kept emphasizing about it, was something the company practically never focuses on today. It was all about the price.

'The world's easiest-to-use computer is now the world's easiest-to-own," was one advertising line on Apple's site at the end of 1998. "Blows minds. Not budgets."

Apple pushed how you could have an iMac for $30 a month, with no down payment, and no payment at all for almost four months.

Maybe Apple was worrying unnecessarily about whether the iMac would attract customers — or maybe Apple had its strategy spot on. For when the numbers were in, the iMac was a hit.

In its first year on sale, almost two million iMacs were sold — and Apple's market share doubled to 11.2%.

"Almost as important as the sheer number of iMacs being sold was who bought the computers," wrote Owen W. Linzmayer in the 2004 "Apple Confidential 2.0" book. "[It] was revealed that 29.4 percent had never owned a computer before, and 12.5 percent previously owned a Wintel clone but not a Macintosh."

So Jobs took Apple from its death spiral and into success. Before the iMac, buyers had to be conscious that Apple was likely to die, and their resulting hesitation to buy Macs was a key reason that was true.

After the original iMac's launch, a whole new market who hadn't heard of Apple's problems, and didn't care, were now buying.

Ripoffs and the future

No good success goes un-copied, and there were of course PCs that were released specifically to capture a piece of that iMac-buying market. None of those manufacturers saw any deeper than Bill Gates had, though, and consequently they made standard, regular PCs that just added bright colors and translucent casings.

It wasn't enough for buyers, but it was enough for Apple to sue firms like Future Power and eMachines. The case took a few months, but both companies ceased their iMac-inspired production lines.

The key thing is that what they missed then is what made the iMac then — and still does. It's never color, it is always that deep understanding that computers are meant to be used by people who are far more interested in their work than in the specifications.

You have to have good enough specifications, good enough technology, but when you sell on processor speed, you lose out to rivals. When you sell on what an iMac can do, you win.

And right at the heart of every iMac from that 1998 model to today, is a very particular design ethos. "Let each element be what it is," Steve Jobs told Jony Ive, according to Linzmayer.

Jobs wanted to keep radically updating the iMac and in autumn 2000, he and Ive were discussing what the next model should be. Walking through his wife Laurene Powell Jobs's garden, Jobs told Ive that "each element has to be true to itself."

"Why have a flat display if you're going to glom all this stuff on its back?" he said. "Why stand a computer on its side when it really wants to be horizontal and on the ground?"

Jobs then said that the New iMac "should look like a sunflower."

Today's iMacs don't look like any kind of fauna. They're close to razor thin, at least compared to those squat, fat, bulbous first iMacs.

But they're still one single device, plus keyboard and mouse, which works for consumers, professionals, scientists and students.

The iMac is forever and always, an all-in-one that is one for all, whether it's the original model with a PowerPC processor, or the latest with Apple Silicon.

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Thomas Sibilly

Thomas Sibilly

AppleInsider Staff

AppleInsider Staff

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

37 Comments

Loved the Pixar lamp iMacs.

But the best iMac I ever had was the G5. It was designed to be repairable and upgradable by the owner. Noisy though. and the first intel that replaced it was basically unrepairable. This situation did not improve until about 2010. It still wasn’t easy, but you could do it. After that forget it.

They still haven’t beaten that iMac G4’s floating display arm. That computer got a lot of sales in customer service/kiosks for that reason alone.