The A18 in the iPhone 16e is not the same as the A18 in the iPhone 16. Here's why the act of chip binning helps Apple while also creating variants of the same chip for different products.

The launch of the iPhone 16e was a thorough modernization of what is practically the spiritual successor to the iPhone SE 3. It's an upgrade that brought many areas of the budget iPhone option up to speed with the flagship range, the iPhone 16.

However, while it is stated as having an A18 chip powering things, it's not the same A18 chip as used by its stablemate, the iPhone 16. They are labeled the same, but they're certainly different.

That process is called chip binning, something many chip makers do to maximize their production yields. While there's no guarantee Apple's using the technique with the A18, it seems like a reasonable thing for it to do.

Here's how chip binning works and benefits Apple.

Perfect imperfection

Creating new hardware is a difficult and resource-intensive process, regardless of whether it's a processor or another module that slips into an iPhone or iPad.

However, in seeking to create perfect chips, issues can creep in. A batch of chips on a wafer could theoretically all be perfect, but manufacturing variances can lead to some of the chips having issues.

Think of it like a production line for chocolate bars. While most will go through the entire production process perfectly fine, some may not be fully doused with a layer of chocolate, or have broken biscuit sections, for example.

Those bars with errors are pulled from the line, so they don't get packaged and sold to customers, who may end up complaining.

It's the same problem for chips, in that not every chip made on a wafer will be exactly as Apple designed it. This could be due to many factors, such as the quality of the silicon wafer, to the equipment used, environmental changes, or even issues with the design itself.

While a chocolate bar is very cheap to produce and potentially dispose of, the same cannot be said for a chip. Each piece of etched silicon is relatively expensive to make, whether its created correctly or has an issue.

Rather than wasting a chip, it can still be salvaged.

For the A18, the issue could be with one of the GPU cores, rather than the CPU or Neural Engine. If that is the case, Apple can simply make it so that the damaged GPU core is not accessible, reducing the total core count from five to four.

Doing so effectively means it's a chip that would otherwise meet all of the specifications to be used in the iPhone 16e, but not the iPhone 16.

To Apple, this means it doesn't waste money or materials on chips that don't meet the standard for use in the iPhone 16. To TSMC, the chip foundry, this helps increase the overall yield from each wafer as well.

Imperfect perfection

While chip binning can be used to repurpose a damaged chip and minimize waste, it can also be used to purposefully damage a chip. This could be down to simple supply and demand.

Take the iPhone 16e for example. If Apple has a commercial hit on its hands, it will need to order more chips to work with the model. However, if it's relying on chip binning of lesser-quality A18 chips, it will quickly exhaust its supply.

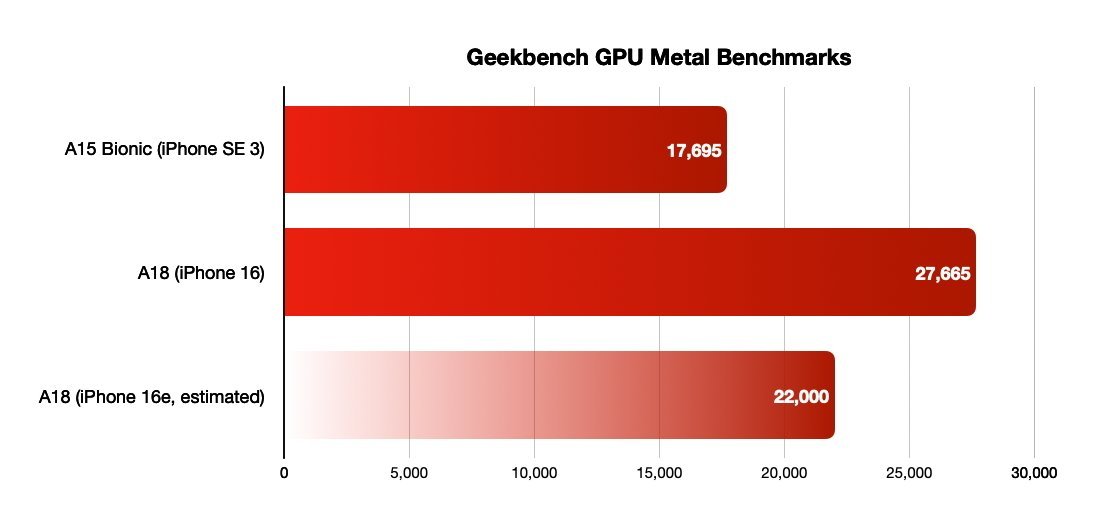

With four cores instead of five, the iPhone 16e's A18 will have lower graphical performance than the A18 in the iPhone 16.

With four cores instead of five, the iPhone 16e's A18 will have lower graphical performance than the A18 in the iPhone 16.Instead of leaving customers disappointed, Apple could make the move of purposefully chip-binning perfectly healthy A18 chips. It can cut off access to one of the GPU cores, effectively making it have the specifications needed for the iPhone 16e.

This may seem like a waste, as consumers will probably prefer to have a full-fat A18 in their iPhone 16e instead of a neutered one. Apple, however, would prefer there to be a difference in performance between the iPhone 16e and iPhone 16, so consumers will willingly pay more for the better device.

A common practice

Chip binning isn't a new technique, as it's one that has been around for quite a few years. Other chip producers, such as Intel and AMD, often employ the technique to make as much use of the entire silicon as possible.

An Intel chip intended to be a Core i5 may not meet the performance criteria for the i5 tier of chips. Instead, Intel could reduce the core count and offer it to consumers as Core i3 chip instead.

This is also not the only time Apple has been suspected of chip binning for itself.

In 2020, Apple introduced the A12Z Bionic, an update to the A12X chip used in its iPad line. It was soon discovered that chip binning was at play.

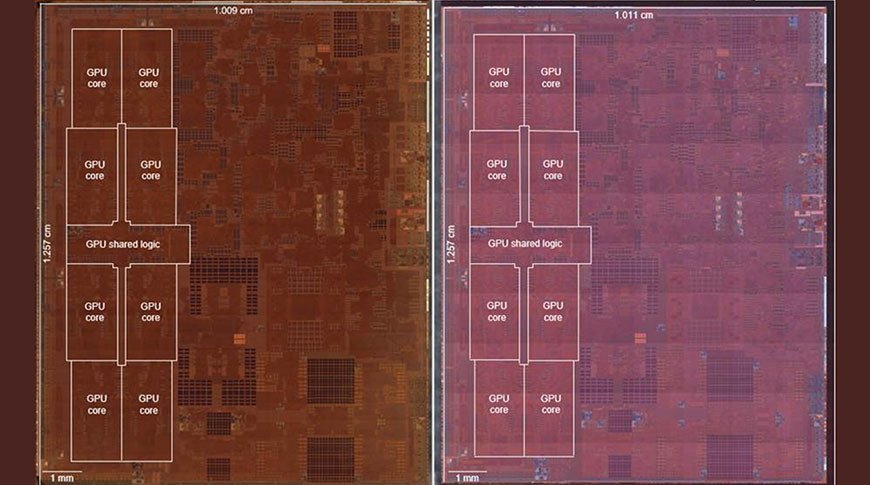

A 2020 die comparison between the A12Z and A12X showing identical GPU layouts - Image Credit: TechInsights

A 2020 die comparison between the A12Z and A12X showing identical GPU layouts - Image Credit: TechInsightsThe A12X was designed with a seven-core GPU, however, the A12Z was given an eight-core GPU.

Apple didn't design a brand-new chip when it came up with the A12Z. It turns out that it's exactly the same as the A12X.

The A12X was made with eight physical GPU cores on the chip, but one core was either binned due to manufacturing issues, or deactivated if there was nothing wrong.

When it came to the A12Z, Apple instead either used chips that didn't get binned or otherwise reactivated the unused core on the chip.

This gave Apple a "new" chip to introduce to the public.

There are even instances going back to April 2012, where the A5 chip used in the Apple TV was a single-core affair. However, Apple had put two cores on the die, and simply deactivated one of them.

However, Apple doesn't always employ chip binning to introduce variances in the same generation of chip.

One investigation in October 2024 determined that the A18 wasn't a chip-binned A18 Pro, with the dies having considerable designs.

This doesn't necessarily mean that Apple is or isn't using chip binning in the A18 destined for the iPhone 16e. It is, however, the easiest method available, especially given the asymmetric three GPU configuration.

Efficiency and normality

Chip binning could sound like a waste of performance to consumers. Outside of making potentially weaker chips into usable and sellable lesser versions, it can also be potentially denying an extra bit of performance.

But, as a common practice in chip production, chip binning is an essential resource and cost-saving exercise. One that can also provide a cheap way to offer chip variants without too much effort.

It's a process that's here to stay. While some may not like the lost opportunity and feel robbed of performance, it's also needed to avoid unnecessarily raising the cost of production.

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

-m.jpg)

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

-m.jpg)

7 Comments

If the chip doesn't include all operational capabilities then it should be considered defective and either disposed of or sold for no more than half its fully functional cost. If someone tells me a fully functional A18 SoC only costs $100 why does the rest of the iPhone cost so much? Dropping the cost of the binned SoC in half to $50 is chump change. Apple needs to justify its cost based on materials especially since the iPhone is no longer a unique device. Most of the iPhone is either the same as the previous version, very close, or was easy (not expensive) to upgrade. Someone is reaping the benefits of every new Apple device.

Interesting article. I think I would quibble with the wording a bit however. This article connotes that "binning" is just about making use of bad chips, making it sound negative. However, binning can be thought of as optimizing the use of high, average, and lower quality chips in a very systematic way. Another reader used the example of different classes of vegetables, and that's not a bad analogy. Another would be beef. The very highest quality cuts are sold to restaurants paying a premium, other cuts as sold with different labels at different prices. The lower quality cuts are not "defective," they just aren't as desirable as the best cuts.

This is an excellent explainer that includes the fact that Apple uses binning to allocate chips between related SoC designs. https://www.techspot.com/article/2039-chip-binning/

Now, I am not an engineer and I could be wrong about this (shocking!), but based on this I hazard a guess that how binning affects the 16e is something like this: chips that can run at some specific speed (or higher) (within some temperature range) are used for the "real" iPhone 16 models, while ones that only work reliably at lower speeds are used for the 16e and are clocked at a lower frequency. That is, the difference between the chip in the 16e and the 16 is probably not just one missing core; all the cores are running just a little bit slower. And not because Apple wants to release an inferior product, but because they want to make efficient use of chips that aren't quite as fast.

As I said at the top, this is a quibble. But it's not a question of whether they 16e is using a "binned" chip (as if it were a chip otherwise destined for the waste bin). Rather, the chips that go into all the iPhones are "binned" (categorized into a bucket based on performance) and the best ones go into the most demanding phones.

If I've got any of this wrong, I welcome the enlightenment.