Microsoft's former chief executive Bill Gates mused this week that it would have been the "natural thing" for Microsoft to have been the "standard non-Apple phone platform." But he's wrong, and here's why.

Gates: Microsoft should have been richer despite its incompetencies

Gates' comments to a VC firm this week stated that being the software platform that served as a competitor to Apple in mobile devices "was a natural thing for Microsoft to win," and suggested that if only Microsoft had been quicker to react to iPhone, Windows Phone could have claimed a $400 billion position as Apple's primary competitor, rather than the Android global collective ostensibly led by Google.

Gates is revered for having earned lots of money, but his comments on what "should" happen in technology are about as faulty as the rest of his vision for the future always was. It's hard to point anyone in the right direction when you have no moral compass.

When Apple took on the U.S. government to avoid being forced to provide backdoors to incompetent spy agencies who can't keep track of their own software, Gates offered the shameful pandering take that Apple should have just meekly complied with the U.S. Justice Department because, "terrorists." It turned out that FBI Director James Comey and the DoJ were lying, willfully misrepresenting the issue to the public in a failed bid to undermine any semblance of personal privacy.

While Gates later regretted looking bad for his comments, Apple's Tim Cook boldly reiterated that the DoJ's smear campaign against Apple was "rigged" and wished he'd had the opportunity to destroy the government's case in court.

"People have values, corporations are made of people, and therefore corporations should have values," Cook stated, describing a concept entirely novel to the tech industry, where previous moguls like Gates blatantly flouted laws, consent decrees, and any responsibility for their actions with the same callous disregard for morals and ethics on display at today's Facebook, Google, Twitter, and Uber.

Are software licensing empires natural?

Gates did acknowledge that "the greatest mistake ever is whatever mismanagement I engaged in that caused Microsoft not to be what Android is."

A contextual interpretation provided by Tom Warren of the Verge attempted to shift Microsoft's blame in losing out in the Post-PC mobile world from the period of Gates' own administration of Microsoft, which largely ended in 2006, to that of his successors.

Gates himself incorrectly perpetuated the idea that his company's success in the 1990s was "natural," with the Verge adding on the flattering but farcical idea that that the broadly-licensed operating system model of Microsoft's Windows was effectively usurped by Google because Microsoft failed to act fast enough in the years after Gates had stepped down as its chief executive.

Writers for the The Verge commonly like to say that Google's free Android software is the "dominant" platform in smartphones, entirely due to the fact that Google's licensees, along with anyone using code from the Android Open Source Project, represent a united bloc in shipping unit volumes of devices that should be counted as a collective and attributed to Google.

This Android ideology seeks to claim legitimacy for the Google empire by citing the history of Windows PCs. That allows it to portray Apple, the only significant phone maker not using Android, as being in the same position it was during the rise of Microsoft's monopoly over PCs: a sort of oddball that's on the brink of doom, which will soon be entirely taken over by commodity because of the natural law of "good enough" mediocracy established by Windows precedent.

The reality is that Android licensees today aren't really dominating anything. The future certainly isn't being laid out for us by Google's latest version of Android. Instead, the world is watching— and slavishly trying to copy— Apple. That's evident when you look at Huawei phones, new features in Android Pie, and even Google's own Pixel phones— which deliver a couple of camera app features in what looks like an iPhone knockoff from two years ago.

Android also isn't dominating phones in commercial respects. Last year, Android's largest licensee Samsung generated $8.8 billion USD in profits on sales of $87 billion from its IM Mobile business, mostly phones but also tablets, ChromeOS netbooks, and Windows PCs. China's leading vendor Huawei also generated $8.8 billion USD in total profits from sales of $107.4 billion, a little less than half of which was from its mostly-phones consumer segment. Google's own Pixel phone sales are negligible.

That compares to Apple's annual net income last year of $59.5 billion from revenues of $265.6 billion, mostly from iPhones. To say that Android is "dominating" anything is outstandingly absurd. Apple is more commercially successful and important than all of Android's various licenses put together.

Ten years ago, Apple was also more commercially successful and important than the world's Symbian or JavaME licensees put together, and anyone trying to counter that Symbian and JavaME retained tremendous "market share" of unit sales would be hard to take seriously.

It's no different today just because Android is the new broadly licensed mobile OS. It's only worse because Google can't even charge anything for it and exercises little effective control of the global installed base of "Android." It can't even mandate 18 months of handset security updates among its licensees.

Things were quite different back when Apple was competing against Microsoft and a global array of Windows licensees. Back then, Apple's revenues and profits were a tiny shred of Microsoft's, or its Windows licensees. For people whose brains formed during the Windows Everywhere era of the 1990s, it's extremely difficult to adapt to the modern world where a broadly-licensed software platform isn't automatically "dominating."

Additionally, Microsoft's Windows monopoly over PCs was not "natural" for the company at all— it never really successfully repeated its 'one weird trick' in any other product categories.

"People who are really serious about software should make their own hardware" - Alan Kay, Xerox PARC

Nor was a broadly-licensed software platform monopoly natural for the computing industry in general. Prior to Microsoft's mostly unchallenged reign over the PC market between 1993 to 2003, computing systems were not "naturally" defined by a market-controlling software platform vendor served by an indentured class of "independent" commodity hardware makers who slaved for slim margins.

Before Windows PCs, home computing vendors including Apple, Acorn, Atari, and Commodore all built complete systems using integrated, internally developed software and hardware, often right down to their own custom silicon.

On the high-end, the business markets for computers before DOS and Windows had been dominated for decades by IBM, which similarly integrated its own hardware and software technology. By the late 80s, Apollo, DEC, HP, SGI, Sun, NeXT, and various other workstation companies were beginning to use open source code and sharing underlying UNIX APIs, but continued to largely develop their own software and hardware to ship complete systems that could successfully compete in the market leveraging proprietary capabilities.

So really, when the young Gates' rich mother hooked him up with a business opportunity in the early 80s and he injected himself into IBM's world by offering Big Blue the ability to create a lower-end PC that involved licensing DOS software acquired by "Micro Soft" and resold via a licensing deal at a tremendous profit, it wasn't "natural" at all. It was a highly unusual hustle.

The hustle that nearly strangled all innovation

Once IBM's entry-level PCs were beholden to licensing Microsoft's DOS, the value of the system was no longer being delivered by IBM, but by Microsoft. Gates' company then licensed its DOS to other PC makers, and worked to prevent anyone else from selling alternatives using predatory licensing agreements that explicitly blocked makers from subjecting Microsoft to any real competition.

The only place where Microsoft really faced direct competition was in productivity applications, and in that arena, Microsoft was failing to gain any traction. That only began to change after Apple's Steve Jobs asked Microsoft to work on apps for its new Macintosh, which would give Microsoft some fresh territory to cultivate its new software applications without the intense competition that existed on DOS PCs.

As the PC business grew into an increasingly valuable segment, IBM attempted to develop its own, more sophisticated OS and hardware platforms with PS/2. It continued work with Microsoft to do this, but as soon as Microsoft felt it could do better on its own, Gates' Microsoft dumped IBM and launched its own plans for Windows.

In parallel, Gates's Microsoft also cheated over Apple by not only porting its Mac apps to Windows, but also appropriating all of the work Apple had done to develop the Macintosh and copying it into Windows, nearly verbatim.

Microsoft would later straight-up steal code Apple developed for its QuickTime media platform, creating an illusion of competence the left most children of the 90s thinking that personal computing, the graphic desktop, and media playback were inventions of Microsoft rather than ideas it ripped off, refused to pay for, and failed to even give anyone credit for. Gates was the rich kid that stole everyone else's work and then laughed at them for being so easy to defraud.

Microsoft used its wealth to acquire and destroy competition, effectively turning all of its competitors into Windows licensees with the notable exception of the beleaguered remains of Apple. But rather than using its empire of global power to usher in a golden age of exceptional technology, Gates' Microsoft contently shoved out shitty software designed to be "good enough" to run low-end hardware, launching the era of "for Dummies" books that tried to make sense of a dark generation of garbage technology that promised far more than it ever delivered.

In fact, most of what Gates publicly promised in his role as Microsoft's "great visionary" was totally ripped off from real products being developed by competitors. Then, once that competition was extinguished through Gates' bluffing, Microsoft walked away without delivering anything exceptional.

What Gates did churn out was boring, ugly tech that only appealed to some IT people who saw supporting it as job security. Gates also delivered long, rambling, humorless speeches at various trade shows where he laid out futures that Microsoft would largely fail to deliver. When people say Tim Cook isn't exciting and charismatic on stage, it means they either didn't experience or have forgotten Bill Gates. I dare you to try to sit through even a few minutes of Gates from 2001.

By the early 2000s, Windows had created a global computing empire of pure drudgery. Microsoft's lack of foresight and planning meant that the world was increasingly held captive to viruses, malware, and spam. The only thing that saved us was that Microsoft had been unable to completely destroy one significant PC maker that hadn't yet subjected itself to being entirely dependent on Windows.

Jobs vs Gates on "winner take all"

In fact, there were two. One had a troubled but functioning computer business that desperately needed a modern new injection of operating system technology, and the other had a futuristic OS platform but no real market available to sell its systems. In the final days of 1996, Apple acquired NeXT, bringing the two companies founded by Jobs together.

Gates didn't see anything remarkable about either one, as this "merger" didn't fit his concept of success. The only world he'd ever known was his own model of Licensing Imperialism where one broadly-licensed OS captured nearly all of the value of the rest of the world and ruled over colonies of commodity hardware makers who slaved to crank out whatever his platform dictated to be the reference model for what they should be trying to build.

Underneath Microsoft's global dominion, there was only an illusion of competition. Gates' string of profoundly stupid ideas repeatedly forced Microsoft's licensees to waste their time building terrible Tablet PCs, PalmPCs, Smart Mira Displays, SPOT watches and other unsalable, ridiculous products that were profoundly forgettable. All Microsoft cared to do was to make sure no real competitors emerged, threatening the "winner takes all" notion that there should only be one central power dictating how technology could be sold.

Jobs, on the other hand, refuted Gates' "winner takes all" mindset. In 1997, he told an audience of Apple developers— who mostly despised Gates and Microsoft— that "if we want to move forward and see Apple healthy and prospering again, we have to let go of this notion that for Apple to win, Microsoft has to lose."

Instead, Jobs stated, "we have to embrace a notion that for Apple to win, Apple has to do a really good job. And if we screw up and we don't do a good job, it's not somebody else's fault, it's our fault. So, the era of competition between Apple and Microsoft is over as far as I'm concerned. This is about getting Apple healthy, this is about Apple being able to make incredibly great contributions to the industry and to prosper again."

To Jobs, "winning" wasn't a "take all" goal. It was just the opposite of losing. For the new Apple, "winning" required "doing a really good job."

Microsoft and the Dark Ages of tech

At the time Jobs said those words, that a rather obvious-sounding idea was completely foreign to virtually everyone in the tech industry. And that's because Gates' Microsoft had created the illusion that winning had nothing to do with doing a good job. It just required ruthlessly destroying all competitors in order to perpetuate yesterday's position of power: commercialized, technological patriarchy.

That's also why most of the people recalling that 1997 event describe it as being the time Gates' Microsoft saved Apple with an infusion of $150 million— as if Apple wasn't already sitting on a couple billion worth of ARM stock— rather than being what Jobs actually said it was: a deal to settle Microsoft's various infringements of Apple technology.

That mindset of tech imperialism had also driven the Dot Com bubble of the late 90s, where everyone was rushing to claim territory in order to erect monopoly empires before any competition could arise. Nobody was really trying to "do a good job" or even waste any time planning things out. As the engineering project triangle predicts, you can have it fast and cheap, but it won't be good.

This was also the era that birthed modern Patent Trolls, which similarly sought to create paper empires by leveraging government-granted monopolies based on loosely worded, patented concepts that enabled trolls to tax the work of people who were actually creating value and building real businesses. Most trolls were fed by failed companies that had amassed patent troves but hadn't been able to build anything with them. These were now begin weaponized to terrorize the companies that were actually competent and operationally proficient.

As the 2000s began, every company was trying to be like Microsoft and was deathly afraid of being an "Apple," a company that put too much effort into its products and had to sell them at premium prices. For years, pundits had been offering Apple the same advice on how to be like Microsoft: broadly license its software, produce the most unit sales by obstructing competitors, and then sit back and rake in the profits from having established some sort of monopoly. That's the dreary status quo that existed as Apple introduced Mac OS X and iPod, two sparks that would end up burning Microsoft's monopoly down to ashes, simply by "doing a really good job."

The "natural" failure of Microsoft's Gates-era monopoly

The attempted expansion of Microsoft's Windows empire over the emerging territory of mobile devices— which Gates described this week as being "a natural thing for Microsoft to win," conceptually— was not a battle lost in 2010 after the failure of Microsoft's Windows Phone initiative, as the Verge incorrectly portrayed.

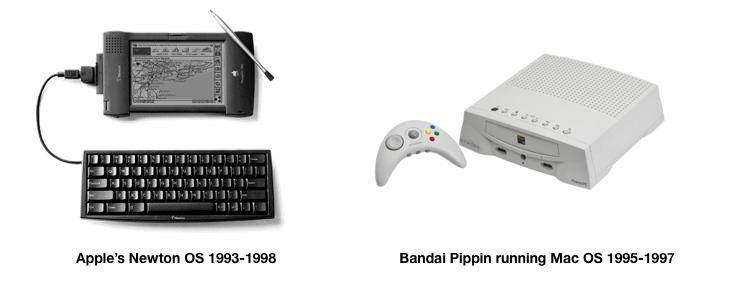

Microsoft's collapsing empire over tech began in the late 90s as Gates attempted to copy or simply acquire all of the talent and intellectual property that Apple had invested— in building the next generation of mobile devices with both General Magic and Newton— in order to leverage these as a way to perpetuate Gates' dream of Windows Everywhere.

The broadly-licensed software platform, the very thing that Gates held up as being "natural" and "winner takes all," was actually the real reason Microsoft failed to successfully usher in a new world of mobility computing. The licensed nature of Windows CE, Windows Mobile, Tablet PC, OMPC and everything else Microsoft attempted in the world of mobility was an albatross around the neck of competitive progress, because it created obstacles between hardware and software advancement by separating them across companies.

Windows CE got started just as Newton ended. Licensing didn't "naturally" help either one become successful platforms

Windows CE got started just as Newton ended. Licensing didn't "naturally" help either one become successful platformsBroadly-licensed software platforms aren't catalysts for innovation. They are impediments to both tight integrations and to the proprietary development of high-quality competition. That's why PCs sucked in the 1990s, and why Androids suck today, and why Symbian and JavaME sucked before it.

The illusion that Windows had been doing such a great job at making Microsoft rich failed to account for the fact that Windows hadn't really created anything. Microsoft didn't introduce the original personal computing model of the 1980s and 90s. It appropriated everything about the Windows PC from others, including Apple, NeXT, IBM, and VMS, and then locked it all down under anti-competitive control that prevented anyone else from adding value and threatening Microsoft's control over the direction of global technology.

That worked for a short period of time, just as a communist revolution can seize a nation's industry and perpetuate the illusion of progress for a while— if it is also able to successfully repress any subversive competition from springing up. But it isn't going to result in a vibrant, competitive market that stokes innovation and delivers the future.

In the same way that Windows was keeping PCs from materially advancing in innovative ways, "Windows Mobile" licensing was keeping mobile device makers from competing effectively. Under a broadly-licensed operating system— the very thing that Gates still holds out as an ideal thing to have in computing— hardware makers are only competing in an illusory fashion, because they are constrained by the same software platform from either using uniquely tight vertical integration or a superior software layer or advanced hardware to stand out.

That's the same problem Android has, which is why Android phones all look like whatever ideas Google appropriated from Apple's work from the previous year. The broadly-licensed operating system is a curse on innovation. It has destroyed any progress in Android tablets, watches, clamshells, netbooks and wearables. And the only place it's working at all is in copying iPhones, which Android copied as shamelessly as Windows copied the Mac. It's easy to copy, but it's hard for a copier to innovate something new.

In the exact same manner, Windows failed Microsoft in tablets, watches, clamshells, netbooks, and wearables. It also failed on phones and PDAs because Windows achieved its one copy with the desktop PC and was stranded there, the same way Google's Android can't make it past copying Apple in phones.

Newton vs iPod: the natural problems of licensed platforms

Some of the key work that defined Apple's first Macintosh did originate elsewhere: Xerox PARC. Apple partnered with Xerox to take its advanced ideas and commercialize them into a mass-market consumer product, which Apple had experience in doing but which Xerox researchers knew nothing about. The result was a product that radically moved the needle forward in technology.

After the Mac, Apple worked on what it expected to be next: the mobile, paperback-sized Newton MessagePad of the early 90s. One thing that most people don't know about Newton was that its "Newton Intelligence" software platform was designed to be licensed in the model of Windows. But that didn't actually help, any more than Apple's parallel plans to license its Mac OS to other hardware makers, including Bandai's Pippin.

In fact, both licensing programs played a part in hamstringing Apple's products because they limited what Apple could do on its own, or how secret it could keep its development roadmap. Jobs pulled the plug on Newton in 1998— after first reabsorbing what had been a subsidiary of Apple actively licensing the platform to other manufacturers. He also killed Mac OS licensing. It wasn't just that Jobs "didn't like licensing." He had presided over years of OS platform licensing efforts at NeXT and knew first hand the problems those efforts caused.

Three years later, Apple introduced the iPod as a new mobile device, with no platform licensing plans at all. At one point Apple sold iPod with HP branding, but it never licensed it out as a software platform. Initially, iPod itself included a licensed chipset platform and a third party, licensed embedded OS: Pixo. But as Apple developed the product, it stripped it of external dependencies and increasingly sought to own and control its principle technologies. This proved to be incredibly prescient and tremendously successful.

Microsoft tries the Apple approach

Microsoft sought to compete against Apple's iPod, first with its own licensed platform involving Windows CE, referred to as "PlaysForSure," as if Microsoft were approving partners' licensed devices as being reliable in playing back Microsoft DRM. That was a failure, for all of the same reasons noted about Windows outside of PCs and Android outside of phones.

Microsoft then changed its strategy to be more like Apple's. That started with Zune, a first party product that did not involve any licensed software platform. It too failed, but mostly because by that time, Microsoft was too late and couldn't catch up. But the development of Zune wasn't as constrained by third parties as it would have been if Microsoft had been trying to license a Zune OS out to a bunch of competitive partners in parallel.

In parallel, Microsoft found some significant success with Xbox, a franchise that, like Zune and iPod, was not a broadly licensed software platform but instead was a vertically integrated, complete system in the model of Apple's products.

And while Gates and the Verge would like you to think that Microsoft's biggest mistake was "not being fast enough" in 2010 with Windows Phone, the reality was that Gates' Microsoft was building Windows Mobile smartphones back in the early 2000s. They were just really shitty products. Gates biggest mistake was, in the words of Jobs, "not doing a really good job."

Back in the day I once wrote a critical piece about a Microsoft shill-columnist that offhandedly stated that he was making too many excuses for Windows Mobile. He wrote me a note defending himself, mostly emphasizing the point that he agreed that Windows Mobile was really terrible and impossible to defend. Windows Mobile was that awful.

Microsoft's Windows Mobile licensing program was a key reason why it was so bad. In part, it was truly awful software. It restrained all of Microsoft's licensees across the entire nascent industry of smartphones from innovating. Microsoft's market power not only helped make Windows Mobile phones really bad, but also created a status quo of shoddy mediocrity that made it easy for Blackberry, PalmOS, and Nokia's Symbian to also sit back and complacently crank out terrible products.

The peak of licensed software platforms

Note that Blackberry was licensing Sun JavaME and Flash Lite on its phones; Palm was licensing its own PalmOS out to others— as well as, bizarrely, licensing Windows Mobile; and Symbian was also licensed across a variety of makers. All of these companies and their licensees were constrained under the wet blankets of licensed software platforms. That's what Gates is now saying is both "natural" and "winner takes all," even though he presided over that mobile era at Microsoft where he knew that neither of those things were even remotely true across the entire decade of the 2000s.

There was no winner "taking all" when Apple appeared with iPhone in 2007. There was a broad array of licensed platforms that each offered horrible software selections including simple $15 card games and media players and basic productivity apps for $50 or more each. The mobile world that existed when Gates was the CEO of Microsoft was the exact opposite of everything Gates described as "natural" today.

That collective incompetence left an opening for Apple to enter an entirely new space with iPhone. Within about three years, Apple had effectively destroyed any demand for Blackberry, Palm, Symbian, and Windows Mobile. The only thing that could eventually begin to compete with Apple was Google's copy of Apple's work, hiding behind the Android Open Source Project as an initiative Apple couldn't directly sue for patent infringement.

Pundits today like to give Android equal credit with Apple's iOS— and often most of the credit— for wiping away Windows Mobile and its peers. But Android didn't even begin matter until all of iPhone's competitors were effectively gone, in 2010. Android was the only thing left that companies like Samsung, Motorola, Sony, LG, and other Windows and Symbian licensees could use to make iPhone copies.

Yet a decade later, it's not Android that is dominating the mobile world. Android effectively doesn't even matter in tablets, watches, clamshells, netbooks, and wearables, nor in TVs or video game consoles or anywhere else it was supposed to matter. All it is doing is continuing to make low-end knockoffs of iPhones in high volume at nearly zero profit for most of its licensees. Only an ideological sycophant would describe that as "dominate," which is why the Verge loves to keep saying that.

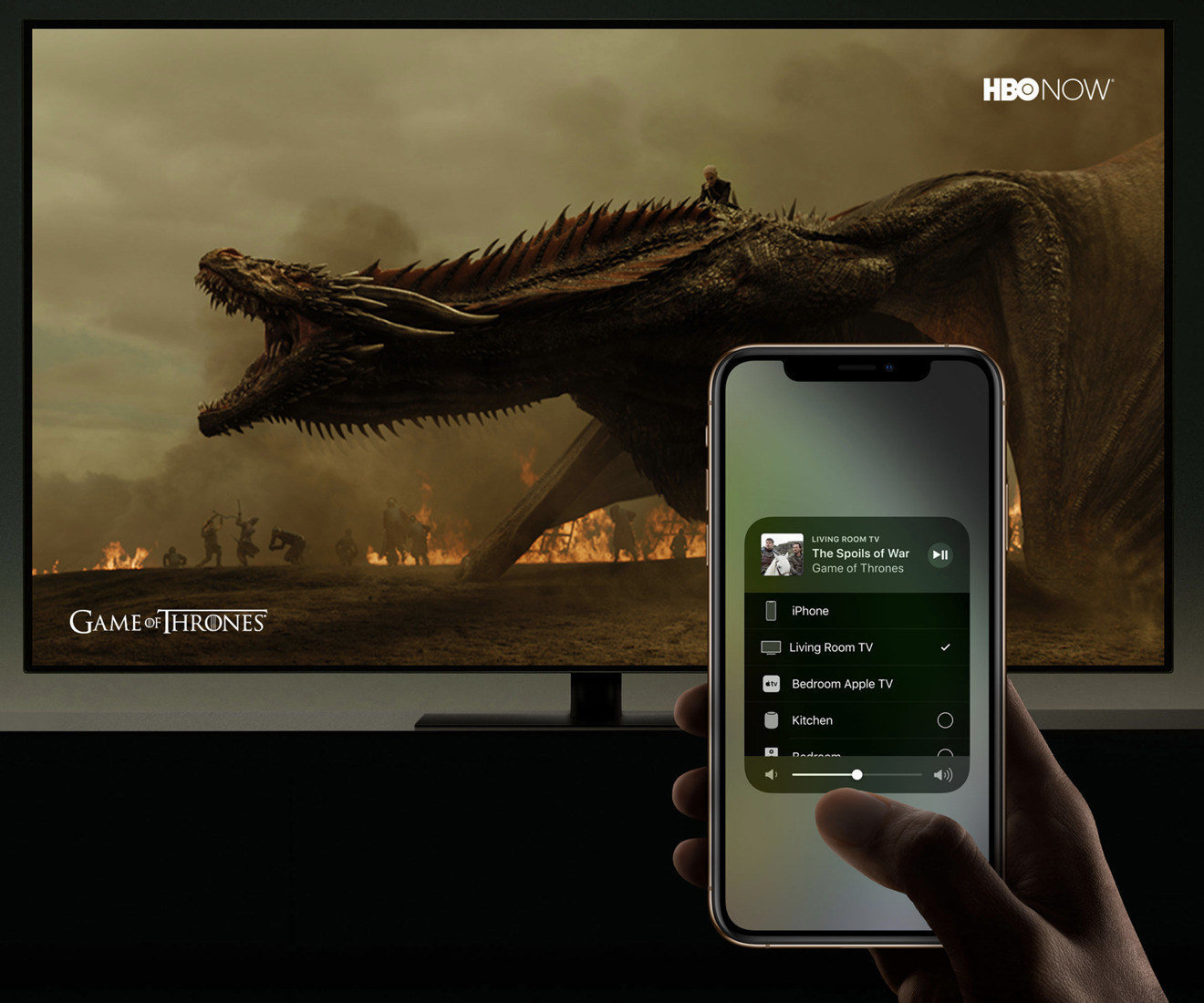

Unlike Microsoft, Apple was able to make it past PCs. It also made it past iPod, iPhone, iPad, Apple Watch, Apple TV, and is now moving into the living room with HomePod and expanding what appears to be a broadly-licensed software platform to people who can only think of ideas in terms of those defined by Microsoft.

But Apple's recent move to license technologies like AirPlay 2 and its new TV app across other companies' platforms is not comparable to Windows or Android. It has far more in common with the technology Apple has previously produced to expand the value of its own devices. That included the original QuickTime for Windows, which expanded the market for multimedia created on Macs; iTunes for Windows, which expanded the market for iPod and later iPhone; and Apple Music, which provides an app for Android users so they too can subsidize the costs of streaming commercial music.

None of these things is constraining Apple's ability to innovate. The new macOS Catalina radically changed how iTunes works on the Mac while keeping the Windows version the same. Apple has enhanced its Apple Music service across its devices with AirPlay 2, AirPods, HomePod, Siri integration, Shortcuts, Continuity, and more, none of which is constrained by Apple Music's support for Android playback.

And so while the Verge is desperately— and rather bizarrely— working to portray Gates as a past hero of technology and Android as the rightful heir to his legacy in establishing a herd of third rate commodity hardware makers building products that all run the same software platform developed and driven by a surveillance advertising company, the reality is that their fantasy view of reality is not just bonkers, but dangerous.

The radicalization of Android

Taking the ideological delusions at the Verge to a whole new level, Nilay Patel wrote that Gates' comments "makes the case to regulate the hell out of platform companies."

His concerns weren't addressing the problems of YouTube promoting child exploitation or social media networks allowing targeted hatred campaigns. No, his concern was that some companies were too competent, and that the government should get involved to pick winners by legally mandating compatibility platforms. Western governments should socialize the costs of Google's Android by forcing Apple to accommodate whatever loser ideas Google is suggesting but can't get to stick on its own.

Patel specifically cited examples of Apple's iMessage, YouTube, and Facebook, all of which have few competent alternatives. Google and its Android partners have provided garbage alternatives to iMessage, and it's hard for anyone to stop using YouTube and Facebook and expect to find a commodity version elsewhere offering a comparable audience.

But is that a problem government is good at solving? EU bureaucrats thought they could solve the privacy issues of web cookies by forcing websites to ask every visitor to run through all their options and pick which cookies they wanted to accept. They effectively turned a problem into an inept catastrophe without solving anything, just entrenching the practice of cookie surveillance on the web by normalizing it with forced "Accept and move on" buttons.

Governments should be regulating toxic e-waste, privacy abuse, and human exploitation, not propping up failed billionaires by forcing everyone else to license their work, just because "journalists" like getting free review equipment shipped to them to play with on a daily basis.

Recall that Patel was the same Verger who both called Apple Watch's Milanese Loop band "ridiculous" and railed against Apple dropping iPhone 7's headphone jack, calling it "user-hostile and stupid." He demanded that users "vote with their dollars" to make sure Apple would be financially crushed by his own ability to orchestrate outrage over events he feared might end up bad for Android, because he thought a new wave of Lightning-only headphones would hurt the market for Androids. He failed to grasp what Apple was doing with AirPods. He writes far beyond his understanding of subjects.

Jean-Louis Gassee took Nilay Patel to task for his fashion critique of Apple Watch bands, and Patel responded with profanity and personal attacks

Jean-Louis Gassee took Nilay Patel to task for his fashion critique of Apple Watch bands, and Patel responded with profanity and personal attacksPatel's "vote with your dollars" boycott targeting iPhone 7's headphone jack ended up being as effective as the collective pandering of the Verge to sell any significant number of Google Pixel phones over the past three years. But now, Patel has further radicalized his position of demanding support for Google regardless of its ability to actually compete in the marketplace.

"If you can't send a signal to the market by voting with your dollars," he wrote, "then you should vote with your vote, and push politicians and regulators to put strong rules in place around privacy and self-dealing, and break companies up to create more competition for user trust and goodwill inside those rules."

What does that mean in the context of the Verge and its contempt for iMessage? Should Western governments regulate chat apps so that Apple would be forced to give Google the ability to shovel its "losing albeit dominate" Android SMS alternative into iOS? Do we want any government issuing fiat decisions on what companies can do, when the issue at hand is simply app protocols that can better be sorted out by a free market, and not YouTube radicalizing terrorists or Facebook distributing violent videos from hate groups?

The anti-iMessage political campaign being waged by The Verge sounds a lot like basic Silicon Valley populist libertarianism, which demands that nobody be regulated at all apart from one's own competitors that are outperforming you due to doing better work. And that one's own favorite platform ideology should be subsidized by legal decree so that everyone else has to prop up failures you think should be dominating. Or basically, straight up Soviet Communism run by failed economic planners who don't like any competition with their ideas.

No Mr Gates, it's functional markets that are "natural"

It's good to take a minute and recall that Microsoft's truly dominant control over technology was challenged by the U.S. federal government in the Windows Monopoly case. That went on for years and established that Microsoft did abuse its monopoly position.

Yet, the solution didn't come from breaking Microsoft up into Windows and Office companies. If it had, we might still be under the control of government-mandated Windows licenses that would restrict every product we could buy, without any real competition to Internet Explorer or Word. We'd still have all the same problems, but from two divorced companies.

Instead what happened is that Apple— a company most people had written off as beleaguered — did "a really good job" and singlehandedly cracked open new consumer markets with iMacs and iPod and iPhone, which then burst into the corporate enterprise with BYOD. And it was Apple's iOS that created a mass market for the modern new mobile browser, along with an App Store promoting a vast number of custom, innovative apps that companies could use as alternatives to Office.

Android offers a competitive alternative knockoff of everything Apple has done. Samsung and Huawei are also both working on their own proprietary operating systems. We have vibrant competition in mobile technology, which is supposed to be the "natural" outcome of a fair and free market. We don't need another Microsoft seeking to be the "winner takes all" imperialist, nor do we need to be subjected to government intrusion to pick winners for us in a communal planned economy.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content

67 Comments

Good article

- Gates book "The Road Ahead" (published in 1995) did not even mention the tsunami of the Internet that was about to happen. Gates was completely caught off guard. He thought the "Super Highway" would be something semi-proprietary that Microsoft would bring to the market

- Windows OS code is a venerable spaghetti shit show. This was why Vista was a complete disaster. It could never be brought to mobile like Apple did in porting OSX to iPhone. Their sloppiness finally caught up with them. It is the Job's metaphor of painting the side of the fence you cannot see

- It was a $150M investment from MS (not $150K) The day is coming when Apple market cap will significantly and permanently exceed MS. Just a matter of time. I remind myself every time I walk past the empty MS store in the mall. And, how Google is systematically taking down MS office from below

Wikipedia,

"After the book was written, but before it hit bookstores, Gates recognized that the Internet was gaining critical mass, and on December 7, 1995 — just weeks after the release of the book — he redirected Microsoft to become an Internet-focused company; in retrospect he had "vastly underestimated how important and how quickly the internet would come to prominence".[3] Then he and coauthor Rinearson spent several months revising the book, making it 20,000 words longer and focused on the Internet.[citation needed] The revised edition was published in October 1996 as a trade paperback,[6] with the subtitle "Completely revised and up-to-date.".[3]"LOL

I will always hate Microsoft for all the time I spent trying to troubleshoot my Windows PCs in the 1990s. The funny thing is, I was an investor and big advocate at the time

“As the PC business grew into an increasingly valuable segment, IBM attempted to develop its own, more sophisticated OS and hardware platforms with

PS/2OS/2. It continued work with Microsoft to do this, but as soon as Microsoft felt it could do better on its own, Gates' Microsoft dumped IBM and launched its own plans for Windows.”