The debate over whether or not to have the so-called "Right to Repair" guaranteed has both sides offering some compelling arguments for and against the introduction of support-related laws, but for the moment, the consumer loses out while the dispute rages on.

What is the right to repair?

Put simply, the "Right to Repair" is an argument that consumers should have the ability to make repairs to devices and hardware they own, without having to resort to using a process provided by the device's manufacturer. This also typically extends to cover taking the afflicted device to a third-party repair center that is unaffiliated with the manufacturer to conduct a similar fix, an option that is slowly becoming unavailable to consumers.

It was relatively commonplace to expect users could repair broken devices on their own a decade ago, as consumer devices were far simpler to maintain and modify. Back then, there was more freedom to open up a broken toaster or other device using some common tools and a bit of knowledge, with a relatively low fear of breaking the device completely, causing more damage, or risking life or limb in the process.

As electronics miniaturized and became both more complex and fragile, it became hard for most users to fix hardware issues themselves, and instead relied upon services provided by the manufacturers, such as AppleCare and the Apple Store's Genius bar.

Manufacturers also become more reliant on consumers using their own services for repairs, dismissing attempts for home user repairs and those by unauthorized repair centers that have not gone through vendor-supplied training as effectively voiding the warranty of the product.

The evolution of designs also means the components used in devices are usually custom to that item, rather than a commodity component, meaning the only real source of getting a legitimate replacement would be through the manufacturer's own service channels. As they are not typically open for use by consumers, nor by third-party repair centers that haven't gone through the prerequisite training nor are willing to adhere to the manufacturer's agreements, it effectively means only authorized repair outfits and the company's own service network can acquire the right parts.

Advocates of right to repair want manufacturers to stop penalizing consumers for fixing devices they own. There are also calls for manufacturers to open up their supplies of components to consumers and unauthorized repair centers, as well as to offer up support documentation so those attempting to do so have every opportunity to get the fix right via the correct and approved method.

iCracked, a repair outfit acquired by insurer Allstate in February, is a supporter of right to repair bills.

iCracked, a repair outfit acquired by insurer Allstate in February, is a supporter of right to repair bills.Efforts have led to various attempts to create new legislation forcing the right to repair to be upheld, and for device producers like Apple to give consumers the ability to carry out their own repairs.

Proponents of the efforts also claim enshrining the right to repair in law would also help reduce waste, as it would give an alternate option to the usual choice of consumers subjecting the device to a potentially expensive repair or throwing it away and buying a new version.

The harmful argument

Naturally, manufacturers are largely against the idea of right to repair. Ignoring a potential loss of revenue from servicing, as well as protecting intellectual property, the main arguments against implementing the legislation fall into both the difficulty of repairing the goods and that of public safety.

The complex nature of modern electronics means a repair may require the use of specialist tools, or require a certain knowledge to successfully diagnose and fix a problem. An attempted repair could potentially result in not only damage to a replacement component if mishandled, but also to other components within a device that may have been functioning properly beforehand.

The second argument, which Apple reportedly leaned upon in its lobbying against a California right to repair bill, claims an inexperienced consumer could easily hurt themselves with the complex hardware. As an example, the lobbyists suggested that an accidental puncturing of the lithium-ion battery could be quite a health hazard.

While this can play on the legislator's memories of Samsung's Note battery fiasco, there are other instances where a ruptured battery has been the cause of an issue. Though rare, there have been instances where Apple Stores have been evacuated following a battery rupture.

An incident in a Chinese electronics store where a customer bit down on a replacement iPhone battery.

An incident in a Chinese electronics store where a customer bit down on a replacement iPhone battery. There is also the famous incident of January 2018 in a third-party repair store in China, when a consumer bit down on a replacement iPhone battery, seemingly to check if it was genuine. Luckily no-one was seriously hurt during that event.

"Batteries are dangerous!" says Apple

Apple's take on batteries being the reason why it isn't standing behind right to repair on smartphones is idiotic, and appealed to lawmakers who continuously demonstrate that they have exactly no clue about technology. Are cellphone batteries dangerous? Sure, at some level, but they aren't grenades — and are certainly safe enough for millions of us to carry in our pockets without thinking twice about it.

All self-repair has some level of danger to the repairer or device. If you're fixing your refrigerator, you can puncture a heat exchanger, leaking out all of your coolant. A car on a jack can fall, damaging the car, or crushing delicate human parts underneath it.

If you've got the confidence to repair your $1000 and up smartphone yourself, you should have some level of self-awareness to know that stabbing the battery with a screwdriver is a bad thing. And, you should know that any repair that you, yourself have done, if botched, voids your warranty. You shouldn't expect to be able to effectively bring a box of parts into Apple and get a repair, if you screwed it up.

Security is an issue

This isn't 2000. The engineering and design principles have changed, and external Internet-delivered and data-stealing threats are more common than ever. Apple's hardware and software combinations are increasingly being designed to counter that threat, and that has knock-on impacts on repair. To that end, we've had the Secure Enclave in the iPhone and iPad for years, and the T1 and T2 chips controlling biometric authentication and other features on a large portion of the currently shipping Mac line

Apple has what has been identified as a "Horizon" machine for Secure Enclave association with Touch ID sensors and Face ID. There is a similar calibration process in software for the T1 and T2 that, theoretically, can block repairs — but it appears that isn't the case as of yet.

Unless Apple can guarantee that Horizon and T1/T2 association are complete "Black Box" solutions, with no way to peer inside and glean how Apple keeps devices secure, Apple should keep them close to the vest. Keep those limited to Apple-authorized shops, and the Genius Bars.

But, there are lots of other repairs that don't — or shouldn't — need Secure Enclave association, nor a T1/T2 calibration, and there's no real reason for Apple to restrict repair part access to those.

Design choices

What appeals to one customer, doesn't have any weight for another. Apple makes design choices for a wide array of users, and has decided that thin and light are primary across its mobile devices. This also has an impact on repairability.

The days of Apple using SATA drives on its portable line are long over. On its portable line, it has decided to use soldered Flash storage, secured by the T2. It has also chosen to use soldered RAM, instead of making the computer a millimeter or two thicker.

A few years back, Apple shifted to socketed processors on the iMac, and processors and RAM are upgradeable at varying levels of difficulty depending on the model.

A few years prior to the iMac shift, Apple shifted away from a socketed processor on the Mac mini, and soldered it down. The 2018 Mac mini returns to socketed RAM, lost after the 2012 model year.

We're not even going to talk about the 2013 Mac Pro right now. We want socketed everything on that, but we think that we aren't going to get it.

So, these design choices to appeal to a large audience have had impacts as well. It isn't as simple as buying a hard drive off the shelf or a SSD and tossing it in a broken machine. And, even on the machines with replaceable internal storage, like the iMac, specific models of drives must be purchased, or a third-party thermal sensor must be fitted. If you don't, then the fans at full speed, constantly, will make your day-to-day work sound like you live on an airport runway.

Apple may have a plan

There are good third-party shops, and bad third-party shops. For that matter, there are good and bad Apple Genius Bars and authorized service centers. The former aren't surveilled by Apple, but the latter certainly are.

Apple's own numbers say that there are 1.4 billion devices in daily use floating around. That's a lot of devices that need service per year, and if you live in a populous area, you know that you can see week-long waits to get a Genius Bar appointment.

In speaking with our cadre of service suppliers that provide us data and insight, a high proportion of these repairs are screens, and non-security related fixes. And, the authorized stores are flooded with them, making the experience worse for not just the Apple faithful because of long turn-around times, but the "device as appliance" crowd as well.

Getting iffy parts to turn these repairs around faster, or cheaper isn't good for anybody, repair-seeker or shop alike. There needs to be something in-between full Apple-authorized service shop and unauthorized shops that are forced to turn to shady Chinese sellers, or cannibalized parts from eBay.

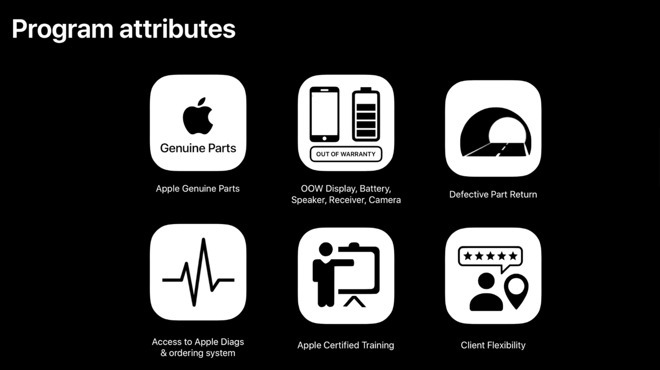

In March, a report unearthed details about a "Apple Genuine Parts Repair" program. The program appears to specifically allow repair shops to do things that Apple-authorized centers have been doing for years, without telling Apple. For instance, there are specific prohibitions on swapping in a "known-good" component not from Apple's stock for troubleshooting, requiring a service replacement part be ordered first.

Specifically, the presentation slides say that providers can "keep doing what you're doing, with Apple genuine parts, reliable parts supply, and Apple process and training." Additionally, the details don't limit the parts to iPhone, iPad, or Mac and include all three.

While AppleInsider has confirmed the authenticity of the slides in the presentation since the original report, as well as the participation of some of the cited vendors in a pilot program dating back to early 2018, we also know that there hasn't been any real evolution in the program, nor any real expansion.

To this end, we'd like to see a supply of non-security parts readily available to a larger subset of the third-party shops than have them now. We'd like to see those iMac thermal sensors, screens, case glass, case parts, buttons, keyboards, batteries, and all permutations of these available to repairers, at least at a board level.

And, to further that end, we'd also like to see releases of at least some schematics for the component-level folks. Apple's reasoning that there are a pile of confidential trade secrets hidden in those diagrams of X86-compatible hardware rings a little hollow.

Around and around

Apple took advantage of governmental officials that don't know any better, have no clue about technology, and seemingly like it that way. That's a shame, and spiking the issue here and there by yelling about potential dangers to the customers won't make it go away.

Apple is right about some aspects of "right to repair," but for the wrong reasons. User security is a factor, yes, but not because of some speculation about safety to unwise governmental folks incapable of understanding the issue or seeing nuance surrounding it. We can't imagine that there will be a rash of battery explosions maiming users because of any loosening of parts availability.

Repair proponents are also partially right about the need for it, but mostly skip over security concerns, plus vastly over-estimate who will do it and who will want to do it. Based on prior polling that we've done, about one in 20 users in 2016 felt comfortable doing any kind of technological repair. So, amping that up for the sake of conservatism in estimates, if four out of 20 given devices get a life extension of two years because of self repair, then design choices that Apple has made along the way that are extending device life only need to extend operational life by six months for the remaining 16 to offset those two years for the four devices. And, we've seen that extension develop over the last 10 years of Apple's design choices.

Like any philosophical conflict, the pair seem unwilling to meet in the middle with a compromise. That may suit their own standpoints and ideals, but it leaves the rest of us out in the cold.

Mike Wuerthele and Malcolm Owen

Mike Wuerthele and Malcolm Owen

-m.jpg)

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Thomas Sibilly

Thomas Sibilly

Andrew O'Hara

Andrew O'Hara

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

37 Comments

Slightly off topic, but worth noting:

Remember how many cracked screens we used to see on iPhones? Not so much anymore by my completely unscientific sampling techniques. And people are holding onto their iPhones longer these.

Nothing new. Its Apple's core values: Making products that just work. Optimizing for "rest of us", not the techies. It seems fair to me to let outlier folks repair iPhones on their own and NOT require Apple to warrantee those iPhones.

I'm curious how the battery biter would know the difference between a good and bad battery? Do only the good ones explode, or do they taste better for some reason?

I've said it before and I'll say it again - there is no justifiable reason Apple can give for charging $600 on a 32gb memory upgrade and nearly $1000 for a 64gb upgrade. That's just out of control. The Mac Mini $1000 base but goes up to $1600 for maxed out memory...a 60% increase in cost when for it could be done under for under $200 by a 3rd party.