Chrome is a perfectly functional web browser, but it and Google's other services deceptively obscure their incredibly deep data-collation and monetization practices from users. Here's how.

Apple works incredibly hard to protect the privacy of its users on the internet. In particular through its Safari web browser, Mail program, Gatekeeper software, and many other features.

Most users are aware of this, appreciate it, and that philosophy may have been a significant factor in choosing to use Apple's products.

Apple's view on user privacy is based around a simple concept, as expressed by CEO Tim Cook, that users' privacy is a fundamental right. "If we accept as normal and unavoidable that everything in our lives can be aggregated and sold, then we lose so much more than data. We lose the freedom to be human."

He has repeatedly called for the US and other countries to enshrine the privacy of users' data into law, building on the model in place in Europe under the General Data Protection Act.

One of the many benefits of Apple's privacy protection is a far, far lower chance of being victimized by actual malicious software. Computer viruses, in the defined sense of the term, are all but unknown for Apple products.

However, "annoy-ware" and even malware exist as a risk — from alarming (but scam) warnings on websites to deceptive software downloads attempting to bypass Apple's security.

In addition to Apple's Gatekeeper software, which generally protects the integrity of installed applications and macOS, the Safari web browser and Apple's Mail program are built with privacy in mind since online communication is the leading attack vector for data-collecting and malicious attempts.

Self-sabotage

Oddly, however, many Mac users still opt to defeat most of these efforts when they choose to run Google's Chrome browser rather than the default Safari or other privacy-centric browsers. Although Chrome for Mac has to abide by some of Apple's privacy rules, which make it somewhat better than the versions of Chrome for other platforms, it is still best characterized as a data miner disguised as a web browser.

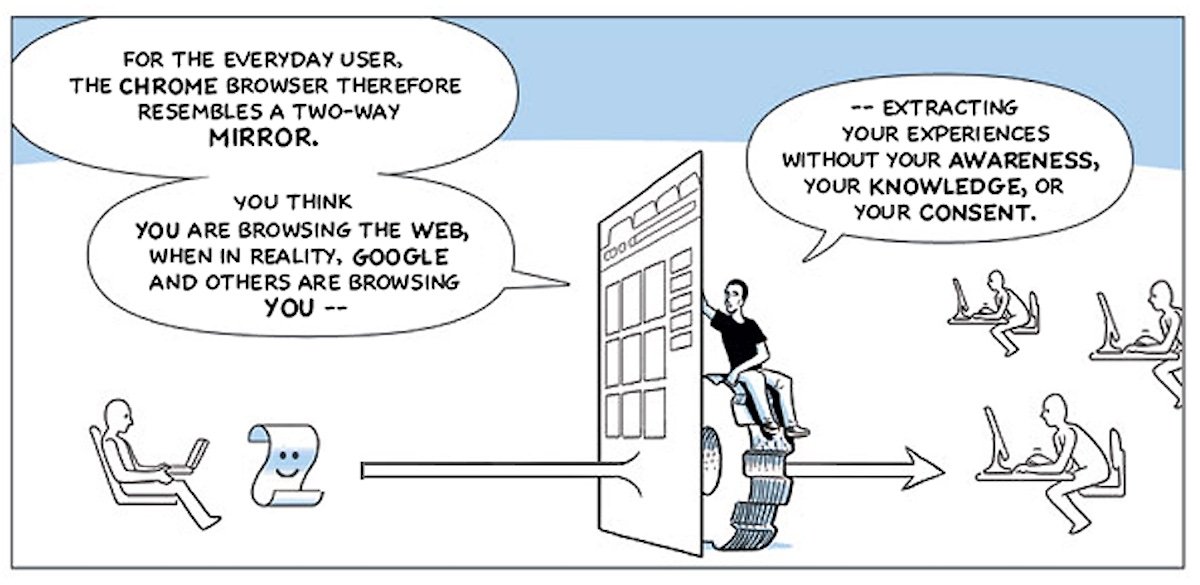

Much of this has been detailed in a webcomic called ContraChrome, created by the very man Google hired to illustrate the power of the program to its employees when Chrome was first created in 2008, Scott McCloud. As a working artist, McCloud was happy for the job back then — but has since decided to update visitors to more accurately reflect how Chrome works now.

Of course, most users understand that if you visit almost any website, some general data about you is collected by that site, primarily for statistical purposes or advertising purposes. This is why the content of most sites is free to view, like this one.

Since Google is the leading engine for web advertising, data gathered from visitors is collected by Google and used to sell targeted advertising. When users see ads, especially when they click on them, the website you've visited gets a small portion of the proceeds, keeping your favorite sites — like AppleInsider — in operation.

That's how the commercial web works and it's an implicit social contract between the site and its visitors. Users agree to have ads shown in exchange for free access to what the website publishes.

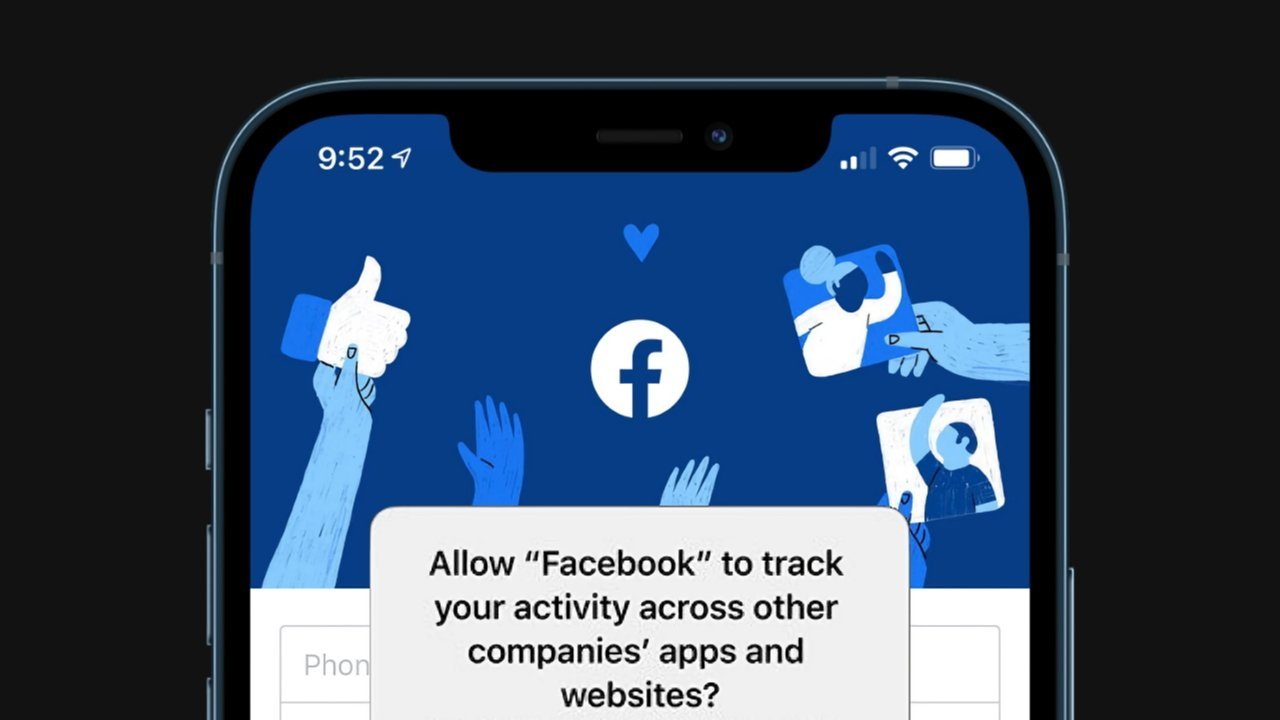

Far fewer users, however, understand that Chrome and those Google-placed ads — or social media sites, like Facebook, TikTok, and Twitter — often continue to collect data about you as you browse the web and have left that last place you hit that cookie. This practice is known as cross-site web tracking.

Safari and some other browsers have the ability to block this tracking. Chrome, being a Google product, allows tracking by default.

The Mac version of Chrome offers block tracking if you invoke it. But, as with its infamously deceptive "Incognito Mode," Google exempts itself and its advertising partners from this, making it into a joke.

How Chrome and Google monetize you

McCloud's webcomic graphically illustrates how Google earns a quarter of a trillion dollars or more annually by giving away free software and services and acting as the leading online ad agency. It starts with the search bar in Chrome, referred to internally as the "Omnibox" because it retains, sends back, and stores absolutely everything typed into it.

You can rest assured that the main Google website's search box, the search on Chromebooks, and various Android features also engage in this practice. From IP address to your purchase history to the videos you watch — and for how long — all of this and much more is gathered into a profile of every user.

To be fair, users can work to try and turn off as many of these privacy-invasive features as they can — but you can't turn off all of it because this is Google's business model and the raison d'etre of Chrome.

More importantly, the vast majority of users wouldn't have the faintest idea of how to turn some of this collection off in the first place.

Now throw in data gathered about you from Google's other products and services — Gmail, YouTube, Google Calendar, Google Photos, Google Drive, the location info you give Google Maps, anything said to Google Assistant, and so on. It's all a lot of random bits until it is collated and processed — and patterns emerge that Google exploits.

It can be argued that behavior manipulation and even modification have been the goal of advertising for all time. Still, Google's super-powered ability to both gather data and draw inferences from that data isn't just for advertisers anymore.

It increasingly sells this data to political entities, foreign countries, shadowy organizations, and anyone with interest in either selling to, investigating or manipulating members of the public.

Apple's built-in protections for when you're online

All these practices are something Safari — and other privacy-centric browsers like Firefox and DuckDuckGo — simply don't engage in. Using Apple's built-in apps and/or the robust market of like-minded third-party apps can vastly reduce Google's data-gathering on you — or at least shape what you do want advertisers to know about you.

Safari has a number of features that prevent unwanted data gathering when you browse the web, and it also prevents third parties from accessing data that Apple has to collect or store on your device, such as your age and location. It blocks sites from web tracking and gives you a Privacy Report showing how much monitoring was blocked, and from where.

Also on Safari is something Chrome doesn't have: a Private Browsing window that is actually completely private. In Safari, no search or website information is saved or shared at all in Private Browsing, so work done in this mode doesn't show in your Safari history and can't be seen by anyone else — even Apple.

Safari also features effective pop-up blocking, but you can exempt select sites from this if they need to legitimately use a pop-up to log you in or for other reasons. There's also a built-in, encrypted password manager that can check to see if your passwords have been compromised or are insecure.

Looking to the future, Apple has worked with others — including Google and Microsoft — to support a new technology called passkeys,. This will eventually replace passwords with biometrics and other secure ways to sign in to online sites, with nothing for users to remember, and nothing for hackers to steal — either from your machine or from compromising websites.

All that said there is one catch in Safari that its non-Chrome competitors don't have: Google pays Apple billions per year to make its search engine the default in Safari. However, it is easy to change that to a more privacy-focused default search — and you should.

We've recently written about some of the best alternative search engines, and many of them can be used as the default. You can also use a preferred search engine as a homepage or bookmark if the one you want is not among the default options.

Privacy-compromising advertising doesn't just live on websites, either — a lot of it arrives through email. Once again, Apple's features in its Apple Mail program work to protect your privacy there as well.

One of the biggest and recent changes in Mail has been the option to Mail Privacy Protection, found in Mail's settings. This hides your IP address and location, loading graphics that would normally gather where you are behind a proxy and blocking the email from notifying its sender that you opened it.

You can also employ the Hide My Email feature if you are an iCloud+ subscriber. This is for times when you need to communicate by email to a given entity, but it's unlikely to be a long-term relationship — like a hotel reservation or a newsletter.

It creates a false email address to use when corresponding that forwards to your real email address, preventing the other party from ever knowing your real email. You can create as many as desired and simply delete them when they've served their purpose — even making a note about which entities you've used which fake email address with.

Of course, it is difficult-to-impossible to fully utilize the web and other online communications with complete privacy. Apple, in particular, has tried to make it easy for all levels of users to restrict excessive data-gathering they mostly don't know about and generally knowingly agree to.

Using Apple's built-in protections and apps, along with other apps and search engines that have non-invasive data policies, is a good start for every level of Apple user. We'd also suggest minimizing your use of Google products and services and employing a VPN whenever you're using public Wi-Fi networks to not only protect your privacy but enhance your online security.

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

-xl-m.jpg)

-m.jpg)

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

33 Comments

I don’t care what the product

I don’t care what they say

If you use Google anything you are being spied on.

Chrome, Android, Maps, Docs, doesn’t matter

They have been caught lying about it too many times.

I do not like WebKit browsers, which is why I’ve been using Firefox for years. I used to use Safari but the changes they made a few years ago, turned me to use FF full time. Even on my i devices.

Using anything Google defeats any privacy issues. IDK why people even attempt to use anything Google.

I avoid all Google and Microsoft software, but I use the Google and Bing websites occasionally. What worries me is that I may want to experience the upcoming AI breakthroughs like GPT, and using such software will probably be just as invasive as a Google Chrome Browser. This is how those nosey companies might be able to get their hooks in me, unless Apple comes up with its own version of GPT that respects our privacy. Go Apple!