Privacy and security are at the forefront of Apple's products. While it is difficult to pinpoint precisely when the focus on privacy began for Apple, Steve Jobs made it a clear value during an All Things Digital conference in 2010:

"I believe people are smart and some people want to share more data than other people do. Ask them. Ask them every time. Make them tell you to stop asking them if they get tired of your asking them. Let them know precisely what you're going to do with their data."

Data and privacy go hand-in-hand. The more control a user has, the more private a person can be. Users choosing to keep their data private should not sacrifice ease of use, and each update showcases Apple's efforts in this space.

Other companies either don't acknowledge privacy or paint invasive features as a worthy tradeoff for constant surveillance. For example, Facebook warns users that blocking ad tracking may lead to them charging money for services.

Google has picked up the pace with promising control over user data and privacy to counter Apple's ambitions. However, despite the options Google offers, it is still too little in the face of data brokers, AI data training, and Google's own need to absorb as much data as possible.

Privacy explained

Privacy is a fundamental human right. People should reasonably live their lives without someone or some company observing and logging their every move.

The reality is many companies have built their businesses on data collection and user surveillance, which has gone largely without public notice. Facebook, Google, Amazon, and other billion-dollar companies have profited by collecting user data at every opportunity then monetizing it.

These billion-dollar corporations are not necessarily selling the data they collect directly. It is too valuable to sell off at random, so they silo the data to observe trends used to target advertisements. These trends are invaluable to advertisers who wish to target an individual on a hyper-specific metric like weight, neighborhood, or employment status.

Data collection is harmful primarily because of how data is stored — most companies directly attribute data to some kind of identifier that can be traced back to its origin. As long as the data is reasonably accessible by a company, it can be subpoenaed by governments or stolen by hackers. Data surveillance places everyone at risk of intrusive entities prying into their lives which shouldn't be the norm.

Data collection has become so commonplace that no one flinches at a location request or access to health data anymore. Apple hopes to reverse this pervasive practice through several initiatives: making it harder to track users by default, giving users control, and educating users about their data.

"I have nothing to hide."

Privacy is an individual's ability to seclude information and only provide what is desired to express themselves. There is little doubt that every individual has data they don't want to be made public. Be that health records, sexual preferences, or religious beliefs — everyone has some need for privacy.

Having or wanting privacy doesn't mean you've some criminal activity to cover or reason to hide. The right to privacy exists to protect you from bad actors, not to protect criminals from the good guys.

"Companies know everything anyway."

Companies like Facebook and Google collect a great deal of data about you and your loved ones, but they do not know "everything." The data's value relies upon constant collection and observation, so cutting companies off from that data collection is impactful.

Data collection companies react with public campaigns or harsh criticism any time Apple makes a change that affects data collection standards — with good reason. Every privacy-first feature introduced by Apple is an impact to privacy-invasive companies' bottom lines.

"Data collection enables a free and equal internet."

Advertising does eliminate the need to monetize every piece of content posted online. However, the scale at which Google and Facebook operate may be well beyond any real monetization need.

Apple proposes that indirect advertising using differential privacy and other tools enable just-as-good results. That the incredible amounts of data being collected for targeted ads are not only unreasonable, but it's also unnecessary.

Advertising will never go away, but it can become less targeted. Rather than showing an ad based on an ad profile, companies could show ads based on your region, webpage relevance, or key terms in a search. The web could remain free and open without sacrificing user privacy.

Search engines like DuckDuckGo use ad targeting based on general IP address location and search keywords. The company doesn't collect data about users, nor does it need a profile to find relevant results. For example, a user with an IP address in New York can search for iPhone repairs and be shown information about the nearest Apple Store.

A new threat to user privacy has emerged called artificial intelligence. It proves that while Google and others used data collection to help subsidize the internet with ads, it has taken a turn and now uses that data to train AI without providing monetization paths.

Google's reliance on other people's data is fundamental in ensuring its AI search results work. Yet, it seems the websites and users that help ensure the web is filled with rich and accurate information are being left with no means to make money — going against the very idea that data collection is meant to provide a free and open internet.

The more AI sucks up information from the web and repurposes it for training without due compensation, the more websites will disappear or be forced behind paywalls. The anti-privacy approach to the free and open web has become the arbiter of its downfall.

There is some hope, as Apple revealed its own version of AI called "Apple Intelligence." It relies on local models that run on the user's devices to preserve data privacy and control. If a query must go off device, it does so in an Apple run server built with Apple Silicon that maintains data privacy.

Data that identifies you

There are many ways that a company can connect data to an individual, and most are not obvious. One common misconception about data surveillance is that companies tap into the microphone or camera on iPhone to gather data. Not only is this wrong, but it also turns out data mining and surveillance are much more lucrative than what can be learned through a camera or microphone.

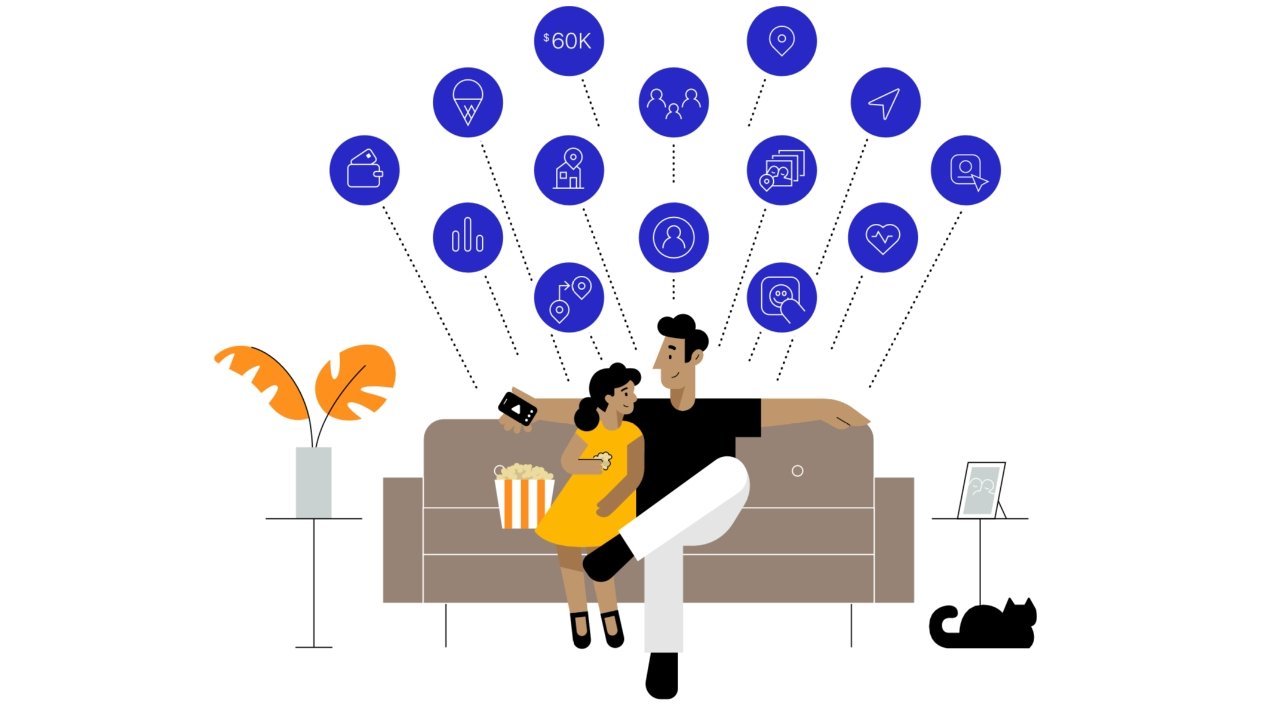

Data brokers buy and collect data from sources for millions of users worldwide, and each user profile may have up to 5,000 identifying characteristics. Everything is tracked about you when possible, from what you bought at the supermarket to how long you visited a friend's house.

Data tracked:

- Name, address, phone number

- Health and fitness metrics

- Credit card numbers or credit scores

- Location information

- Race, sexual orientation, religion, political disposition

- Contacts in your address book

- Photos, videos, recorded audio, or streaming data

- Browsing history

- Search history

- Purchase history online and in physical stores

- Device usage data

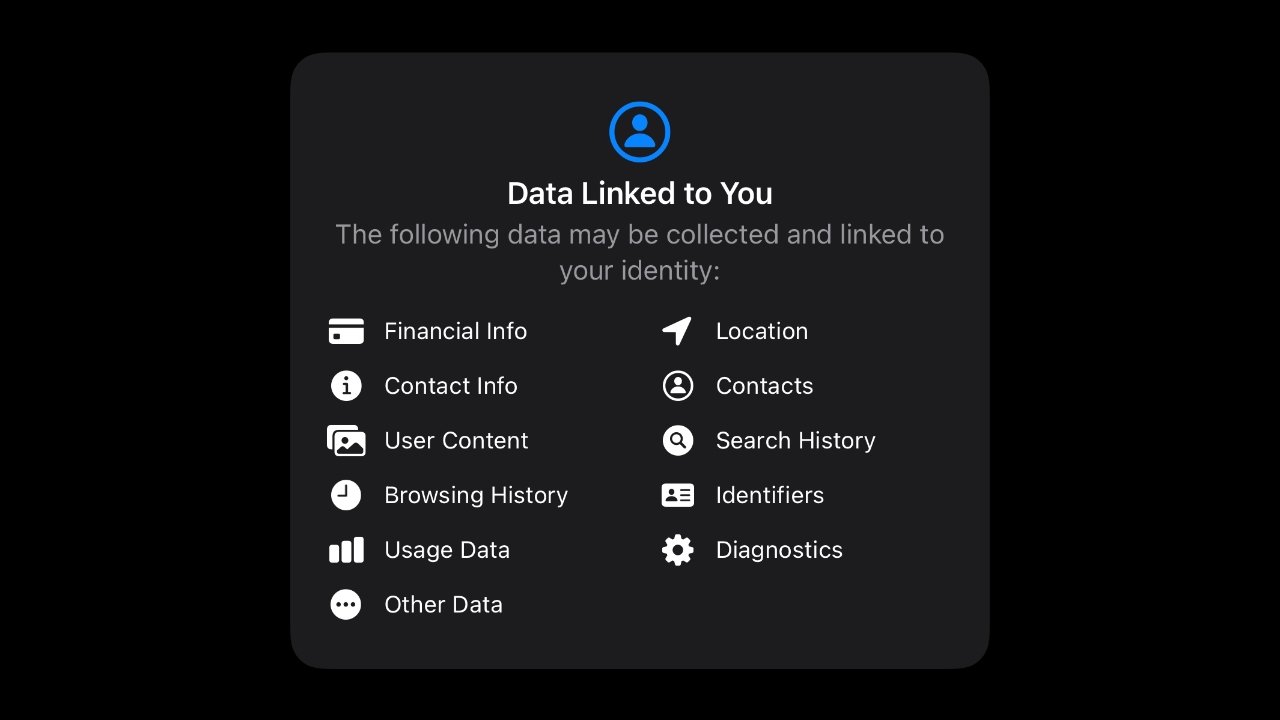

Apple labels these metrics as data that can identify a specific user. Developers are required to report what data is collected and how it is used in their App Privacy Labels on the App Store.

When using Google services like Google Maps and Google Pay, users can be tracked throughout their day. Google can learn where the user goes, what they buy, how much they spent, and when they get home just from an afternoon of data gathering.

Through constant surveillance, Google will develop trends that can be sold to advertisers for billboard placement and email coupons. Essentially, you've just traded a life of surveillance through free tools from Google for a 10% discount on toothpaste.

Ad tracking

Data tracking doesn't stop at personal information or user interactions with apps or devices. Companies use other identifiers to track you like social media trackers, ID for Vendors (IDFV), and Google analytics.

These trackers follow you around your devices by using different technologies like cookies. For example, Facebook and Twitter will log your visit to a website whenever a social media button for the respective platform is present on a webpage.

Apple has taken steps to prevent cross-site tracking despite protests from Facebook and Google. You'll learn about some of the technologies Apple implemented below.

How Apple protects your privacy

Apple devices are built with hardware and software features that focus on privacy and security. From microphone disconnects in MacBooks to iMessage encryption, Apple has you covered.

Encryption and security

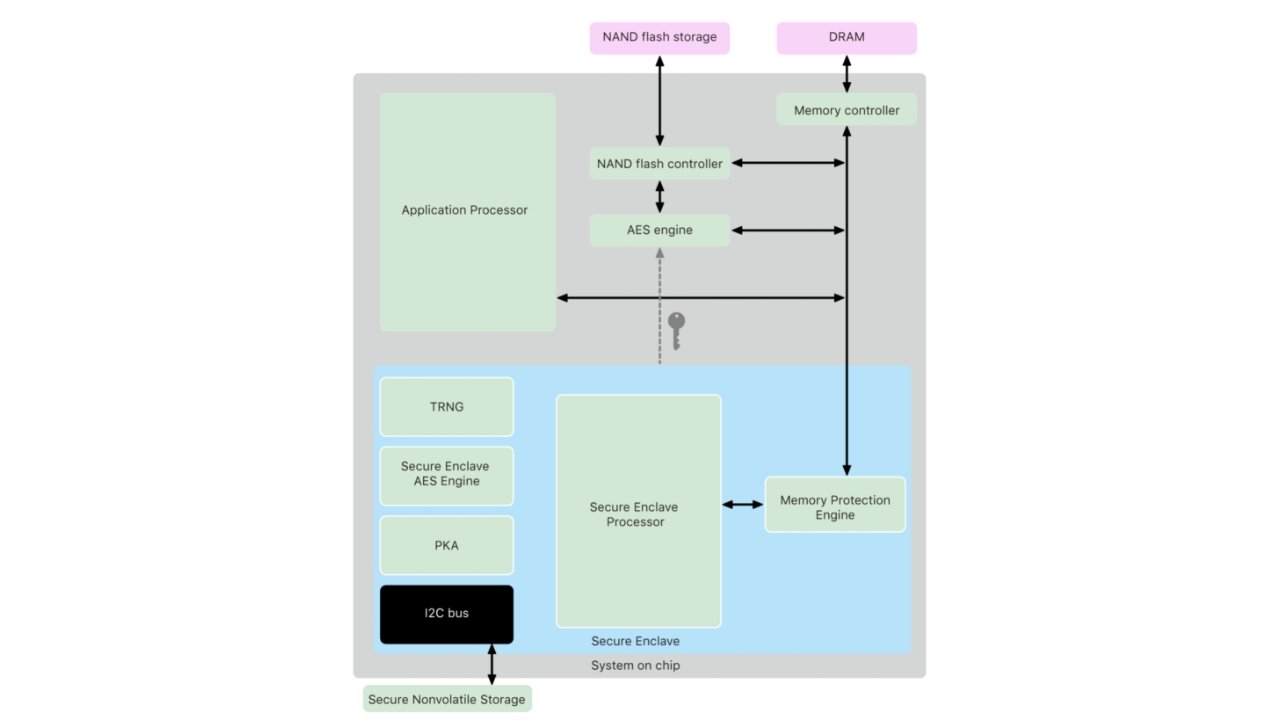

Some essential privacy protections provided by Apple happen in the background. Users do not need to know about the Secure Enclave, end-to-end encryption, or app sandboxing to know that their data is safe on iPhone.

The photos you take, messages you send, and health data you track are all end-to-end encrypted to prevent bad actors from getting to your important data. The Secure Enclave, coupled with biometrics like Face ID, keep your device locked and secure until you've authorized it.

Hardware disconnects prevent the microphone from working when the lid is closed on MacBooks with a T2 processor or M-series chip. Apple implemented a similar iPad feature that causes the microphone to disconnect when a Smart Keyboard or magnetic cover is closed.

The Secure Enclave is found in iPhones, iPads, and Macs. This device operates as a physically isolated entity for storing secure data like passwords, health data, or encryption tokens. Data on the Secure Enclave can only be accessed when authorized via biometrics like Face ID or a password.

When your iPhone or iPad is powered off then back on, most of the data on the device is inaccessible and encrypted. This state is called "before first unlock" and can cause problems for hacking tools like those provided by Cellebrite.

Like Apple and privacy, Apple and encryption have a complicated history filled with controversy.

Differential Privacy

Apple utilizes a system called Differential Privacy that adds random bits of noise to data it collects to disguise the individual data's origin. This practice keeps Apple or anyone who observes the data from determining that a particular data point came from a specific user.

After collecting data on a metric from thousands or millions of users, a trend will appear, and the noise will fall off. Apple will still have a data trend to observe without the ability to trace any single piece of data back to its origin.

Apple's data collection policy differs from other companies that assign identification numbers or even accounts to the data stored in servers. If Apple is subpoenaed for specific information that has been hidden behind Differential Privacy, there isn't a reasonable way for the company to provide such information.

Features studied with Differential Privacy:

- QuickType suggestions

- Emoji suggestions

- Lookup hints

- Safari Energy draining domains

- Safari auto play intent detection

- Safari crashing domains

- Health type usage

One example of Differential Privacy in action came via Apple Maps. Crowdsourced information about road obstructions combined with user data collected from GPS signals and map queries provide live traffic data to users without sacrificing data privacy.

Apple and Privacy education

Apple can't control every aspect of privacy on a user's device without creating severe limitations. Instead, Apple attempts to educate users with pop-ups and advertising campaigns to develop privacy awareness.

Onboarding and user control

When new iPhone users set up their phones for the first time, they are greeted with several privacy configuration windows. They set up data collection controls for diagnostics, Siri, and learn about Apple's policies.

After initial setup, users run into several privacy-related prompts during regular use. Apps will request access to location, Bluetooth radios, and data like contacts. Pop-ups attempt to educate users about the danger of constant access to some portions of data, but that isn't always enough.

With each update to its operating systems, Apple introduces new roadblocks for data collectors and improved tools for users. These updates generate a lot of controversy among ad agencies and data brokers, but courts generally find that informed users and opt-in collection is favorable.

Privacy Labels

Privacy Labels were added with iOS 14.3 and act as "nutrition labels" for users. When a user goes to download an app from the App Store, a prominent box describing the app's privacy details is shown. Users can click on this box for more detailed information about data collection and how the app uses it.

This passive form of data collection shaming has had mixed effects so far. Companies like Google were reluctant to submit Privacy Labels and went weeks without updating their primary apps. Some users flocked to social media to post some of the biggest offenders in data collection, but most users don't know or don't care about the update.

Privacy Labels act as a stop-gap between total ignorance and attempting to read through a dense privacy policy. Companies must submit their own Privacy Labels based on good faith, and Apple will penalize any company sharing fraudulent data with customers.

App Tracking Transparency

Privacy Labels were a passive attempt to educate users about apps they install, but starting with iOS 14.5, Apple took a more active approach. App Tracking Transparency shows a pop-up for each app or service that attempts to track the user and gives them a chance to opt-out.

Users have a tracking identifier data brokers, and ad agencies use to track them across apps and the web. It is called the ID for Advertisers (IDFA), and it is unique per device. Users who opt-out of tracking via the App Tracking Transparency prompt will have an IDFA of all zeros.

Apps have been given the opportunity to educate users why they should opt into data tracking practices but ultimately must show the dialogue giving them the ability to opt-out. Apple will block any apps that attempt to fingerprint users with different methods.

It is estimated that Apple's ATT has reduced social media income by as much as $10 billion in the second half of 2021. Research points to users opting out of data collection when presented with a clear choice.

Privacy Transparency Reports

As a part of Apple's push for data transparency, users can view data requests made by world governments on Apple's privacy website. The report is released annually and is separated by country.

The United States made thousands of requests across four categories — device, account, financial identifier, and emergency.

Most of the requests were made via search warrants or subpoenas. Government requests range from police requesting access to a device's data to the FBI seeking iCloud information about a suspect. Apple reviews each submission and requires that the requested data pertains to a specific portion of the account over a defined time range.

Only in the most extreme circumstances, like in the event of domestic terrorism, will Apple hand over all available data about a suspect. Most of the data Apple has on a person is stored in the individual's iCloud backup since backups are not end-to-end encrypted in the cloud.

Privacy Controversy

Apple attracts a lot of attention from people, governments, and companies due to its actions around privacy. With each update to iOS or its other platforms, Apple is often targeted by many who believe privacy measures could harm businesses or help criminals.

Apple versus Facebook

One significant case is between Apple and Facebook. Once Apple announced its App Tracking Transparency feature in 2020, Facebook started a major campaign against it. Facebook targeted people who don't have a fundamental understanding of technology and privacy with the hope to sway the masses' opinion.

Facebook claims that small businesses thrive when they can target specific demographics using data categories created by Facebook. The company harvests tons of data from users, sifts through it using algorithms, and presents advertisers with targeted groups for ads.

Apple claims that Facebook collects too much data and can accomplish the same goals using different collection tactics or by collecting much less. Tim Cook says that Facebook has an opportunity to convince users to opt into data tracking, so the move isn't anti-competitive.

Facebook started its campaign against Apple by taking out full-page newspaper ads stating that the feature would harm small businesses. It continued by contacting businesses and convincing them to provide statements against Apple's feature.

Ultimately Facebook's efforts have fallen short of legal action. Public reaction to Facebook's complaints has shown it to be a campaign that earned little sympathy from customers.

iMessage child safety

The less controversial feature that shipped with iOS 15.2 was iMessage safety for minors. The feature uses an algorithm to detect nudity in images sent to children and automatically blurs the photo and alerts the child of potentially harmful content.

The child can accept the risk and view the photo, or choose to avoid viewing the photo. It is a feature parents can enable on child accounts below the age of 13, but no one is notified of the image or the child's decision except for the child. A similar warning will appear if a child attempts to send an image containing nudity.

Apple originally intended to alert parents when a child chose to accept or send nude photos, but iPhone users lashed back stating this could lead to abuse or exposing a child's sexual orientation inadvertently. Now, the alert is meant only for the child and to provide useful links and help to children who seek it.

It has expanded so adult users can request potentially NSFW content be filtered in iMessage as well.

CSAM detection (No longer being implemented)

One of the biggest black eyes to people's perception of Apple and privacy was the announcement of features aimed at protecting children. Multiple features were announced at once, which led to confusion and ultimately Apple stepping back from its plans.

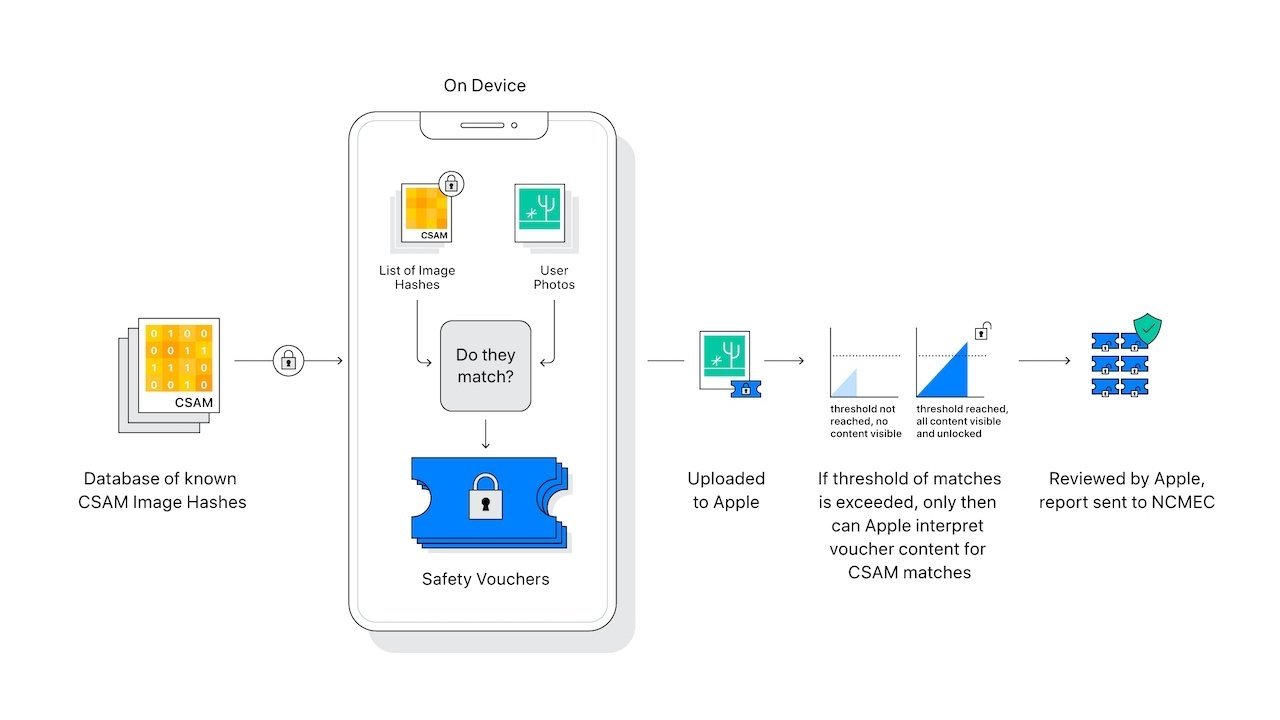

The second feature Apple announced was a new system for detecting Child Sexual Assult Material, or CSAM, in iCloud. Rather than decrypt a user's photo library and compare hashes to photos in the server, Apple decided it would be more privacy-friendly to perform the hash comparison locally on the device.

The initial announcement didn't have much detail about how this system would work, which led to confusion and people combining iMessage child safety features with CSAM detection features. The uproar led to Apple walking back the feature release timeline in order to better explain how the feature would work and why it was being implemented this way.

Every Apple device would contain an encrypted list of hashes, numbers that represent photos. These hashes are made from known CSAM contained in a central database controlled by a non-government organization.

When a photo is being uploaded to iCloud, before it begins its transfer, it is hashed using the same process that created the CSAM hash database. An image hash will be nearly identical every time, regardless of color alterations, cropping, or other methods attempting to obfuscate the photo.

The person's photo hash is then compared to the CSAM hash database, still on device. If an image matches, it gets a positive safety voucher. After an unspecified number of positive vouchers are flagged on the server, the photos corresponding to positive vouchers are sent to Apple for verification. If images are identified as CSAM, authorities are alerted.

The system was produced to prevent violating user privacy by decrypting photo collections server-side to perform hash matching. Any company that stores documents online, like Microsoft or Google, performs CSAM database matching on the server.

Misinformation, confusion, and misunderstanding of the technology implementation led to a lot of protest among Apple users, government officials, and safety advocates. Despite attempts from Apple to educate people about the feature, it failed.

Apple has withdrawn the CSAM detection feature from its update roadmap and will introduce it again in the future once it is sure it will satisfy complaints. Apple and Privacy go hand in hand, but this feature left a lot of people concerned that CSAM detection could lead to privacy violations, photo scanning, or authoritarian control of iPhone systems.

Engineering frustrations with privacy

Apple's stance on privacy creates internal strife as well, according to a report shared in April 2022. Some employees complain that proposed features can be rejected by even junior-level privacy engineers if it doesn't respect a user's absolute privacy on the platform.

One such feature was proposed in 2019, which would allow users to make purchases via a Siri command, but that would require tying voice commands to an Apple ID. Another long-requested feature is the ability to track users as they move between content in the Apple TV app to provide recommendations. Both were rejected on the grounds of privacy.

Some users have complained that the privacy stance also holds Apple back in some feature sets compared to companies like Google. For example, Google Maps has a lot of user data to work with versus Apple Maps, which means Google can make their maps experience much more tailored to the user.

These complaints haven't swayed Apple's stance on privacy, however, since the company still leans heavily into the concept that it collects as little data as possible. It tends to work around limited datasets using alternate methods like differential privacy or voluntary crowdsourced data.

The debate around Apple and Privacy will become even more heated as the company seeks to introduce AI features in iOS 18. Rumors suggest that it will use on-device models and features that preserve user privacy, but it isn't clear how that will be implemented.

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content