Apple claims to be the home of privacy and security, a place where users can feel safe just using their devices without a prying eye. All modern iOS and macOS devices are capable of hardware encryption by design. The debate surrounding Apple and encryption is long but comes down to a simple concept – security and privacy for the user.

Your iPhone or Mac, when configured correctly, will keep all but the worst bad actors out of your data. This also means the good guys can't see your data either, and government agencies are not so happy about this consumer-level protection.

Encryption Explained

Data encryption is a cryptographic process that makes data incomprehensible to anyone who doesn't have the proper keys. This ensures that only the person with the correct passwords can access and read data otherwise, the data accessed is just a mess of characters.

All of this security happens without user input, besides the occasional password or biometric, and is designed to get out of the way as much as possible.

Data can exist in transit or at rest, and so does encryption. Generally, data in transit should be encrypted, which means anyone spying in on your traffic will not see what is passing through.

Data at rest is usually only encrypted if need be, but Apple encrypts the entire device when locked, if it is iOS or iPadOS. macOS users can opt to encrypt their computers using FileVault, and those who own a Mac with a T2 or M1 processor will have encrypted drives automatically.

Total device encryption can be a very processor-demanding task. This often meant users used to have to choose between total device encryption and speed.

Ever since the iPhone 4, this hasn't been the case. iOS devices have benefitted from hardware encryption for nearly a decade now, and Apple uses AES-256, which is what banks use for transactions.

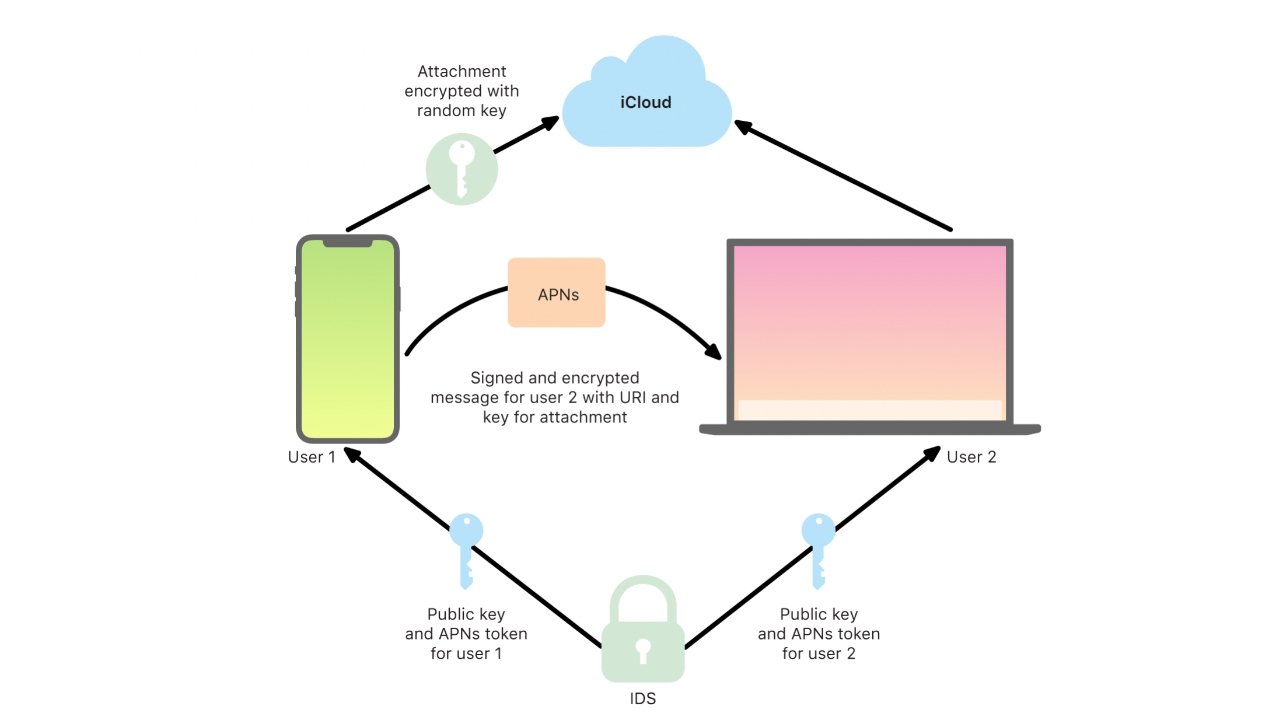

When data is encrypted no matter the state, and the key is generated and stored on-device, it is called end-to-end encryption. This means that the data is secure unless the decryption key is presented. Data like this is usually locked behind the user's Apple ID and Password.

End-to-end encrypted data on iOS includes:

- iMessage and FaceTime

- QuickType Keyboard vocabulary

- Health and Home Data

- Screen Time

- iCloud Keychain

- Siri information

- Payment information

- WiFi passwords

Encryption in the Cloud

While things like iMessage and FaceTime are end-to-end encrypted, other information is not. End-to-end encryption requires that only the party who owns the information has access to the keys, like with device encryption.

When saving data to iCloud, however, things change considerably. Apple always encrypts data in transit and encrypts data stored on its servers, but when it comes to iCloud backup its encryption keys are stored with Apple.

When a user has iCloud Backup turned on for a device, information like iMessages, photos, health data, and app data are all saved in an encrypted bundle on iCloud. The key to unlocking this bundle stays with Apple to prevent a user from inadvertently losing their secret key, and thus all of their backed up data.

This means, though, that Apple does have reasonable access to data when properly warranted by a government investigation.

If and when Apple complies with a government data request, it is often the iCloud backup data that provides the most useful information. Apple doesn't always hand over every bit of data they have, however, but only portions of data specific to the warrant.

Only specific cases ever demand total access to data, and Apple will deny those requests if deemed data requested is not part of the case.

Apple started storing iMessage data in the cloud for syncing. This data is normally end-to-end encrypted when on-device and in transit between users, but if a user elects to have their messages sync across devices, their history is saved to the cloud.

While that history is fully encrypted in the cloud, an encryption key is saved inside of the iCloud backup to prevent data loss. This means that if Apple decrypted the backup, pulled the key from it, then used it to open the synced messages, they could do so.

All iCloud data is managed by the user. If you deem it unnecessary or unsafe to use certain iCloud syncing or backup features, you can toggle each one. Local backup using Finder is also an option, which will let the user encrypt the backup locally, as well.

Users will be aware of their own circumstances and need to determine where they want to store data.

Remember, there is no such thing as a perfectly secure system. Convenience will always reduce overall security, so using iCloud tools can improve your life, but introduce scenarios where your data can be accessed under certain conditions.

Hardware Encryption: T2 and the Secure Enclave

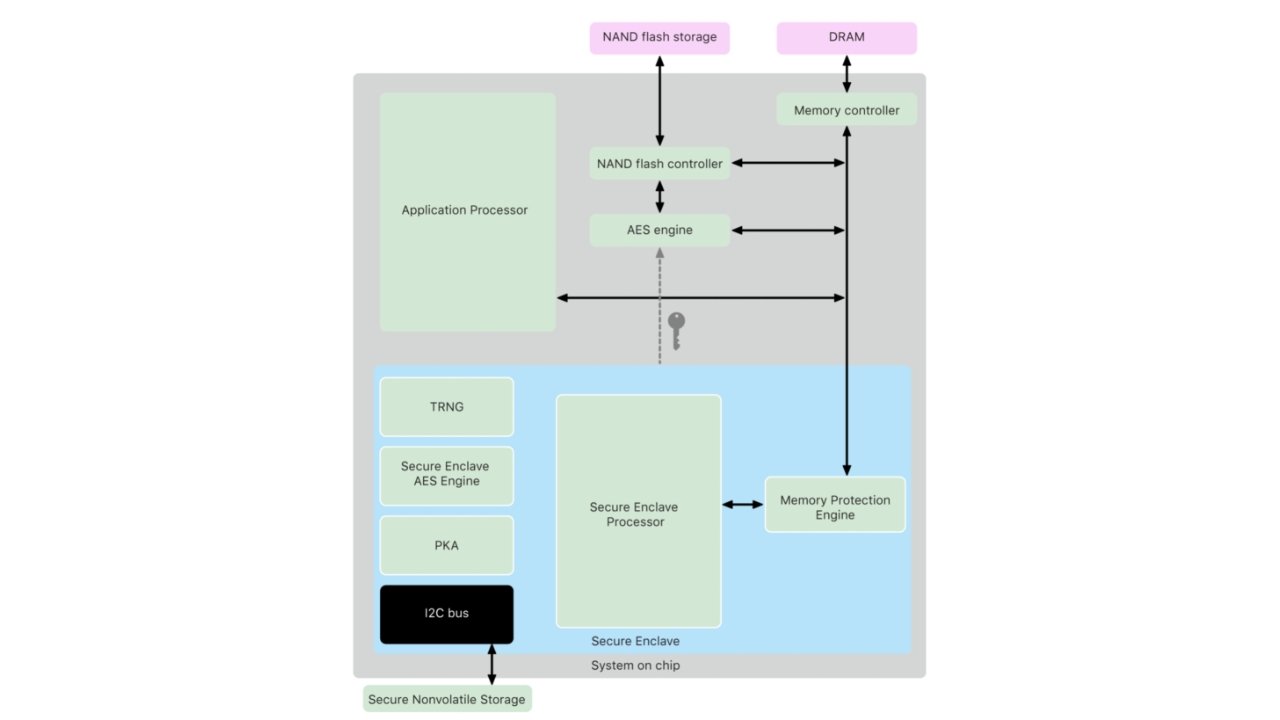

The introduction of the Secure Enclave to the iPhone 5s changed things again. Not only were devices encrypted, but the keys were also stored in a chipset completely separate from the device OS.

This meant that remote attacks were rendered nearly impossible and anyone trying to get information would likely need physical access to the device to even begin a brute force attack.

For any device newer than the iPhone 5s with Touch ID, and devices with Face ID, the Secure Enclave handles all generated encryption keys. A notable exception is the iPhone 5c, which was released after the iPhone 5s, and didn't have the Secure Enclave.

This was the phone used by the San Bernardino shooter, which sparked the entire encryption battle with the US government.

The Secure Enclave acts as a gatekeeper to all of your sensitive information. It holds onto encryption keys, like those used for iMessage until presented with proper authorization like a passcode or biometric.

Even the biometric data used for Face ID and Touch ID are stored using encryption, so there isn't even any record of your face or fingerprint used by the system.

MacBooks with a TouchBar have Touch ID built-in, which means a dedicated Secure Enclave as well. The first generation T1 chipset held the Secure Enclave and handled key generation just like its iOS counterpart. The T1 chipset runs completely independent of macOS and boots separately for added security.

Apple then introduced T2, which breaks away from needing Touch ID as a prerequisite and allows users to enjoy its functionality on other devices. Not only does the T2 hold the Secure Enclave, it manages FileVault encrypted storage and Secure Boot also.

Secure Boot is a very important security enhancement, which prevents illegitimate software or operating systems from loading at startup. It also prevents booting from external media, thus thwarting hackers who might attempt stealing information using alternative booting methods.

When Apple moved the Mac lineup to Apple Silicon, the Secure Enclave was moved into the M-series processor for a more comprehensive System on a Chip. So, the encryption, Secure Boot, FileVault, and other operations performed by the T2 are now handled by Apple's processor.

Apple versus The US Government

San Bernardino 2015 (iPhone 5c)

One of the deadliest mass shootings on record occurred in San Bernardino on December 2, 2015. There were 14 people killed and 22 seriously injured during the attack. One of the perpetrators, Syed Rizwan Farook, left behind his company iPhone, leaving investigators wanting what was inside.

February 16th, 2016 a judge ordered Apple to break into the phone's encryption using special software to be developed by Apple. The iPhone 5c in question was running iOS 9 and did not have all of the security capabilities of the more modern iPhone 6s, and had no Secure Enclave, which would have made access even more unachievable if it had.

What the judge, and ultimately the FBI, was asking for was a new iOS update that would defeat the encryption using a back-door provided to the FBI. Because of this approach, any iPhone running this OS would be vulnerable to such decryption, and the keys given to the good guys likely wouldn't stay in their hands forever.

Apple CEO Tim Cook said as much in his open letter to the US Government the next day.

Apple asserted that they had handed over all of the requested data 3 days after the shooting occurred. They even offered advice on how to force the phone to back up to the cloud, which was ignored.

It was later found out that the Apple ID associated with the iPhone was changed while in government custody, ruining any chance of a backup.

This tit-for-tat battle continued in a very public debate and shed a lot of light on exactly how much the US Government, and more specifically FBI director of the time, James Comey, knew about technology and encryption. Damaging public exposition continued for the following month, leaving Americans to watch as their personal security was debated on a national scale.

On one side, the DA asserted that "evidence of a dormant cyber pathogen" could be found on the iPhone. The husband of a former co-worker and survivor of the shooter said the company phone was "unlikely to contain useful information."

A hearing was set for March 22, so prosecutors could present and cross-examine witnesses over the encryption matter. This was supposed to be the FBI's last chance to convince Congress to force Apple's hand, but the hearing never came to pass.

On March 21, the DOJ asked for a delay to the hearing. An "outside party had come forward with a potential unlock method that would negate the need for Apple's assistance."

Israeli firm Cellebrite was said to be helping the FBI attempt to unlock the iPhone. This raised several concerns over the tool, the government's willingness to work with foreign companies, and the taxpayer dollars spent on the hack.

On March 28th the DOJ withdrew their legal action against Apple, citing that they had successfully gained access to the device. Rumors continued to speculate that Cellebrite helped, citing a $218,000 contract the company made with the FBI on the same day of the hack.

It was never officially confirmed if the data from the terrorist's iPhone 5c was informative or useful in any way, but seeing as there's been little word about the data, it likely wasn't useful. The FBI Director did reveal, however, that the tool was useless for any phone newer than the iPhone 5c.

In April, unnamed sources cited that the iPhone in question didn't provide actionable intel, it did however give investigators more insight into the attackers.

James Comey wouldn't rest, however, declaring the "encryption war far from over."

In December of that year, the U.S. House Judiciary Committee's Encryption Working Group issued a report. It stated, "any measure that weakens encryption works against the national interest." This seemingly, finally, put the encryption debate to bed.

Sutherland Springs 2017 (iPhone SE)

A new administration and new FBI director brought new challenges to the encryption debate, which had nearly a year of quiet before being reignited. Only a few weeks before the Sutherland Springs shooting, the new FBI Director Christopher Wray made his stance clear.

"To put it mildly, this is a huge, huge problem," Wray said. "It impacts investigations across the board — narcotics, human trafficking, counterterrorism, counterintelligence, gangs, organized crime, child exploitation."

On November 5, 2017, another tragedy wracked America as shooter Devin Kelley killed 26 people at a church in Sutherland Springs Texas. The FBI moved quickly and made practically the same mistakes as during the San Bernardino shooting.

Reportedly, the FBI refused to seek help, took the phone from the site to a remote FBI facility, did not ask Apple for information, or perform the iCloud backup procedure defined by Apple previously. 48 hours passed and the critical window for direct help from Apple closed.

On November 9th, Texas Rangers secured warrants for files stored in the shooter's iPhone SE and served them to Apple.

For whatever reason, not even a rumor has appeared about what happened next with this case. Speculation can assume that Apple handed over what data they had, as usual, and told them that unlocking the phone was impossible.

Given that it was an older iPhone even then, the FBI likely was able to procure a way to get inside and avoided another public debate. New evidence found in April 2021 suggests the FBI used a hacking firm in Australia to access the iPhone.

2018

Outside of, or perhaps because of the Sutherland Springs case; Apple began educating law enforcement and the FBI on how to access data from iPhones, Macs, and iCloud. This wasn't a class on hacking into devices, but a basic course of understanding how to request data, handle it after receiving it, and how best to deal with devices.

Apple wasn't done with its fight however, with each new update to iOS and macOS, Apple doubled down on security and encryption protocols. The FBI Director and forensics examiner both stated similar angst towards the company at a Cyber Security Conference in January 2018.

They called Apple "jerks" and compared them to "evil geniuses" that were thwarting the good guys at every turn.

While the "good guys" kept pushing for legislation to weaken encryption, other companies were pushing for new tools that took advantage of known exploits. One such company was GrayKey, which said had a tool that could crack a six-digit passcode in 11 hours.

Companies like GrayKey and Cellebrite tend to sell their hacks for a lot of money, so regular consumers never needed to fear them much. A GrayKey box was sold for $15,000 to $30,000 usually, and Cellebrite hacks were even more expensive.

What complicates this more is that once Apple can patch an exploit used by these tools, they do, and push the patch within weeks to nearly every Apple user on the market.

Pensacola 2019 (iPhone 5 and 7 Plus) to 2020

A gunman killed three people in Pensacola, Florida while in the possession of two iPhones. The shooter, Mohammed Saeed Alshamrani, fired a bullet into one of the devices before being killed himself.

Apple handed over all of the data they had associated with the devices, but the FBI became persistent, again asking Apple to unlock iPhones.

Vocal US Attorney General William Barr made a public request to Apple, stating that they had yet to provide "substantive assistance" to law enforcement. The DOJ was determined to get into the iPhones, claiming that they may determine if the shooter had conspirators.

Barr had been vocal earlier in the year on the subject, saying there must be a way to create backdoors without weakening encryption.

Apple provided an official statement in response to the Attorney General.

"We reject the characterization that Apple has not provided substantive assistance in the Pensacola investigation," Apple said in the statement. "Our responses to their many requests since the attack have been timely, thorough, and are ongoing."

"We responded to each request promptly, often within hours, sharing information with FBI offices in Jacksonville, Pensacola, and New York," the statement asserted. "In every instance, we responded with all of the information that we had."

"We have always maintained there is no such thing as a backdoor just for the good guys," Apple concluded. "Backdoors can also be exploited by those who threaten our national security and the data security of customers."

The letter reiterated many of the same arguments that Apple and Tim Cook had been stating for years. The President even chimed in with a tweet, telling Apple to "step up to the plate" and unlock the iPhones.

An update to the Pensacola case came on February 5th where the FBI stated they still cannot access the data on the phone. The phone was finished being reconstructed after being shot by the perpetrator, which may have something to do with the data not being accessible.

In May, the Pensacola shooter was tied to Al Qaeda using data pulled from one of the iPhones. While the shooter was in contact with the terrorist group, there was no evidence that the attack was an order.

The FBI gained access to this data with "no help from Apple," which means some third-party resource was used. The FBI did not reveal which iPhone was accessed, but a comment from Secretary of Defense William Barr told us that both phones were indeed unlocked.

Apple followed up Barr's comments stating that the Justice Department made "false claims" surrounding Apple's help in the investigation.

Much later, in October of 2020, The Department of Justice and the "Five Eyes" nations released a document making an official request for encryption backdoor access. The document states that those concerned would rather compromise privacy and security for access to encrypted data for the sake of the safety of those citizens.

Late in 2020, it was discovered that public schools had been purchasing forensic tools from foreign companies like Cellebrite to hack into student's and faculty's devices. This unprecedented invasion of citizen privacy is not protected by fourth amendment rights due to how laws surrounding student privacy are set up.

NSO Group and Pegasus hacks in 2021

A hacking tool dubbed "Pegasus" has made the news multiple times over the years for breaching iPhones using a sophisticated toolset to install surveillance tools. Generally, it is understood the exploit jailbreaks an iPhone then installs malware tools to allow remote access to the device without the owner realizing it.

NSO Group is the company that creates and sells hacking software to governments for use "against criminals only." Pegasus is one of those tools, and it was discovered in smartphones belonging to journalists who report on authoritarian governments in mid-2021.

An NSO Group data leak exposed a list of over 50,000 phone numbers linked to people of interest for the company. More than 180 phone numbers belonged to journalists linked to CNN, New York Times, etc. An investigation of the phones belonging to 67 journalists on the list uncovered surveillance software on 37 devices.

The NSO Group denies the allegations that it worked with authoritarian governments to spy on journalists and other non-criminal entities. It called the allegations "far from reality."

Apple sued the NSO Group in November 2021 to hold the company accountable for the surveillance of Apple users. The filing also seeks an injunction against the NSO Group from using any Apple technologies.

These hacks are expensive and require specific conditions to be met before they can be executed. Average consumers need not worry about being exposed to Pegasus or other hacking tools since the level of sophistication and expense generally limits these exploits to national interests.

Where encryption stands

The debate is far from over. Legislation threatens to fight consumer-level encryption in many countries, like in Australia. Giving a key to "the good guys" would mean an eventual leak of such a key to the bad guys too. Then all Apple security would be rendered nearly worthless.

A breach of the CIA hacking tools in 2017 made this reality all too clear. The government promises to protect backdoors provided by Apple even though top-secret CIA hacking tools are being stolen.

According to a January 2020 report, Apple may have been planning to end-to-end encrypt iCloud backup data but decided not to based on FBI demands. Apple has stated publicly before, that encrypting backups might overly complicate security for users, and added that a user who loses their secret key would lose access to all of their data.

Until Apple can find a way to prevent users from losing everything from a silly mistake, it is unlikely that iCloud backups will be end-to-end encrypted.

For the over 1.5 billion Apple device users out there, things are still looking up. Device security is as strong as ever, and all but the most skilled or money-lined hacker can breach that security; even then under only very specific conditions.

Hacking tools and security holes pop up from time to time, but the level of sophistication and local device access required prevents average users from being affected. Generally, most people with a strong passcode and biometrics will never have to worry about their device encryption being breached.

How to protect yourself with encryption

Apple products are protected by industry-leading hardware and software security, but some may feel that is not enough. It's healthy to remain cautious and know what you can do to further protect your data.

Emergency SOS mode

First, know about the emergency modes and reboot shortcuts on your device. If you hold down the volume up button and power button at the same time for five seconds, it triggers an emergency lockdown.

This prevents your iPhone or iPad from unlocking with biometrics, and gives you the option to shut down the phone or call 911. If you shut down the phone, it will be back to Before First Unlock to provide maximum data protection.

This mode is handy for that moment when you might need to hand over your iPhone to a school teacher or an investigator and you feel the need to protect your data. This also helps with police officers who cannot ask for a password but can sometimes legally request biometric unlocks.

Use an alphanumeric passcode

Many forensic tools rely on guessing passcodes on the device using algorithms. The longer your password, the harder it is to crack.

By adding a couple of letters and a special character you'll increase the time it takes to guess the passcode from hours to hundreds of years. You'll still need to remember the password too, however.

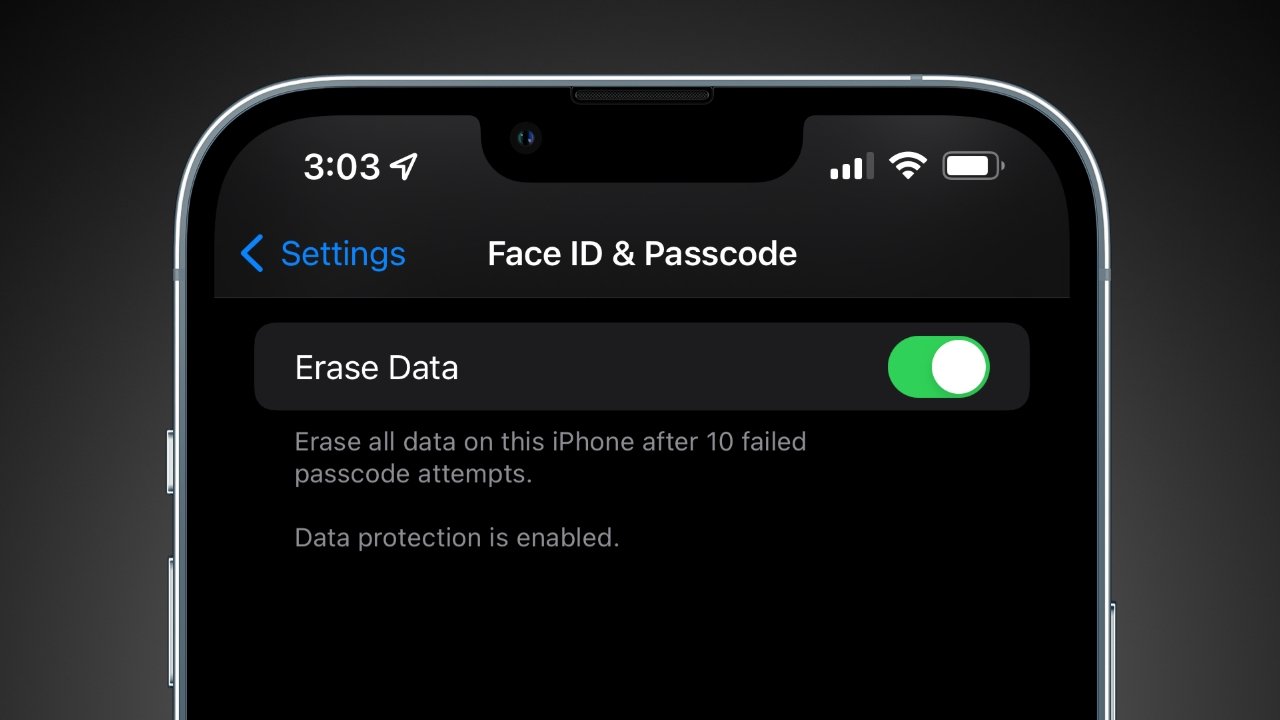

Erase all data after 10 failed passcodes

Users should also be aware of a setting that resets the iPhone to factory settings after 10 failed passcode attempts. After a few failed attempts, you'll be blocked by a timer that gets longer and longer until you're waiting thirty minutes between passcode attempts. No normal iPhone use will accidentally cause your device to erase all data.

Local backups

If you want to go to the most extreme level of data protection, consider removing sensitive data from iCloud. You can perform a local iCloud backup by connecting your iPhone to your Mac.

Doing this will enable a local encrypted option, which will secure the backup behind a password you choose. Forget the password and the backup is lost forever though.

Continue as normal

Apple is already doing everything it can to thwart bad actors from breaching your data. Your iCloud data is safe too, and can only be accessed when a proper warrant is presented.

Use your iPhone as normal and live your life. The likelihood of an average iPhone user encountering a forensic tool or wealthy criminal seeking what's on your iPhone is slim to none. The encryption and security Apple provides are enough to keep your data safe and will only improve with time.

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

Amber Neely

Amber Neely