The jurors deciding the outcome of the second Apple vs Samsung trial haven't yet returned a verdict, but their options are limited to a few possible outcomes, ranging from a fiery thermonuclear blast to a wintery new Dark Ages.

Option 1: Posnerize it; Samsung wins

The first verdict the jury could potentially render is to return a decision along the lines of Judge Richard Posner's in the parallel iPhone-related patent trial between Apple and Motorola.

In that case, Judge Posner decided that, at least in the case of Apple's iPhone, patents should have no value because if they did, Motorola would be left trying to sell Google's indisputably "inferior non-Apple technology" and it would be "catastrophic" if customers had only one source to obtain Apple technology.

Judge Posner decided that Apple should essentially be forced by the government to license its technology to Motorola, which could then bargain for a "fair price" for its use. While Judge Posner's decision was overturned on appeal, the jury in the Samsung case could essentially replicate it by awarding both parties nothing, resulting in another several months of delay before the next trial.

Option 2: VirnetX-style trollin'; Samsung wins

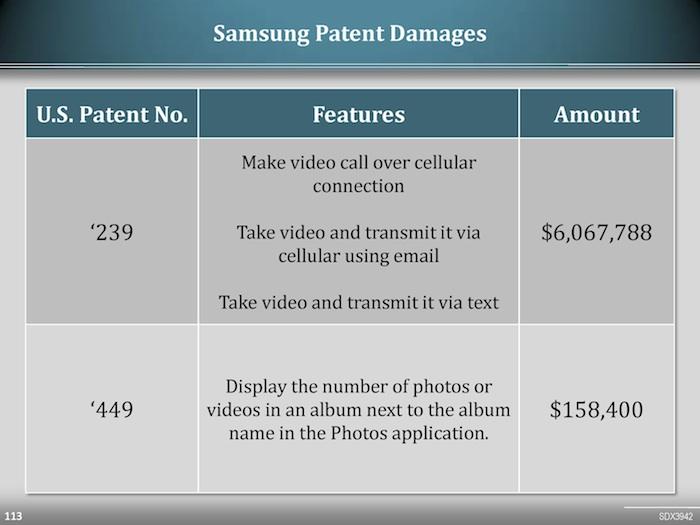

A second outcome, only slightly worse for Apple, would occur if the jury decided to award Apple nothing while taking seriously Samsung's counterclaims for the two patents it acquired for its cynical countersuit-defense after being sued by Apple in 2011.

This would be moderately similar to the VirnetX patent troll case that Apple initially lost (pending appeal) against a Non Practicing Entity that claims it has a monopoly on the concept of using a VPN tunnel to transmit FaceTime video chats.

If jurors in the Samsung trial similarly failed to understand the nature of the patents Samsung acquired in order to present a countersuit of its own, they might return a decision that handed Samsung a relatively small amount of money while giving Apple nothing.

The amount of money Samsung asked for is small because the entire point of Samsung's countersuit was to portray all patents as worth very little, in a hopeful bid to reduce its own liability for infringement of Apple's patents.

Option 3: Money for everyone; Samsung loses

The jury might also select a more charitable possible outcome by "fairly" awarding both sides everything they asked for. In this case, Samsung would get virtually nothing and Apple would be awarded as much as $2.2 billion.

Not only would Samsung end up owing a judgement over twice as large as the first trial, but it would also be branded a serial copyist. Such an outcome would also seemingly have to blunt Samsung's enthusiasm for refusing to negotiate with Apple, because it would now be on the wrong side of over $3 billion in total damages.

Things would be slightly worse for Samsung if the jury didn't award it anything at all in its countersuit, although this would again (just like the first trial) erase Samsung's ability to claim that Apple "also lost" and "also copied" it by infringing "its" technology, too.

Option 4: Holy War; Samsung really loses

A fourth possible verdict could result in awarding Apple even more than $2.2 billion in damages. Apple is asking the jury to determine that Samsung's infringement not only occurred, but was "willful."

As a general article on the subject of willful patent infringement by Timothy M. O'Shea for Lexology noted, "A finding of willful infringement in patent litigation is the nightmare scenario that all defendants fear because it allows the patent owner to request that the judge enhance the damages, up to three times compensatory damages. 35 U.S.C. § 284."

Trebling the $2.2 billion in damages that Apple is asking for would result in Apple taking another $6.6 billion away from Samsung Mobile, or nearly one quarter's earnings. That's a lot of money, but really only a fraction of what Samsung earned in the years following its decision to clone the iPhone 3GS in early 2010.

Samsung's "Crisis of Design" decision put an obstruction in the way of Apple's potential total iPhone sales, but it turned Samsung Mobile around from a failing phone vendor into a powerhouse of profit that has helped carry the rest of Samsung Electronics, while enabling it to prop up a wholly unprofitable series of products designed to copy Apple's other offerings, from a Galaxy-branded iPod touch clone (below) to its various copies of the iPad.

Unfortunately for Samsung, none of its other copies of Apple products have really been profitable at all. Outside of smartphones, Samsung's entire tablet and PC operations are barely breaking even. While pundits are grousing about Apple's flat iPad sales this quarter, the reality is that Apple is earning healthy profits from tablets that no other tablet shipper is capable of even approaching. That includes Samsung.

A substantial blow to Samsung's current strategy of copying its competitors might likely result in an abandonment of the company's increasingly less profitable IT and mobile business altogether in order to focus on its other businesses, including chip components, networking gear, TVs and appliances.

That would particularly be the case once Apple files its third lawsuit against Samsung, arguing another batch of patents and targeting its Galaxy S4 flagship for the first time.

Option 5: Thermonuclear; Samsung really, really loses

On top of a finding of willful infringement, Samsung's worse case scenario would also involve sales bans of all of its infringing products and every substantially similar product variant that also infringed Apple's patents.

A sales ban would interrupt Samsung's entire "copy & cash out" strategy, forcing it to scramble to change how its products work before it could begin selling them again.

While FOSS Patents blogger Florian Mueller has argued that Samsung could easily 'design around' Apple's patents, doing so would still involve some slight effort; otherwise, Samsung would already be doing this across the board rather than spending millions of dollars to pay experts to have the opinion that it doesn't need to do anything and that it owes Apple nothing. Winning a sales injunction against HTC in 2012 caused that company to eventually reach a settlement with Apple, rather than spend the time required to develop workarounds that might (or might not) work to lift the injunction.

Winning a sales injunction against HTC in 2012 caused that company to eventually reach a settlement with Apple, rather than spend the time required to develop workarounds that might (or might not) work to lift the injunction. The carrot of negotiation proved far more tasty than the injunction stick for HTC, and the same decision would very likely be reached by Samsung, were Judge Koh to not preclude the use of such a stick.

However, in the original Samsung case, despite Apple being exonerated from Samsung's accusations and winning its infringement claims against Samsung, Judge Koh still refused to grant Apple a sales injunction against Samsung's infringing products, ruling that Samsung could keep selling its infringing products because she wasn't convinced that they "caused irreparable harm" to Apple in a way that couldn't be addressed in the form of monetary damages, even though years will pass before Samsung will ever have to worry about actually paying those damages.

In the meantime, Samsung can continue to profit from those infringing device sales and work on various fronts to further shave down its potential damages and perhaps even successfully invalidate one or more of Apple's patents using a series of creative strategies that might mean it never has to pay anything at all.

Justice streamlined for speedy delay

As long as Judge Koh insists on a series of scaled down trials that each pare down the evidence Apple can present and streamline the patent claims it can raise in order to speed the cases through the courts as cheaply as possible, without ever allowing Samsung to feel any impact of its actions beyond some transient embarrassment, it's in Samsung's vested interests to keep clogging the court's docket with a series of objections, delay tactics and appeals to ensure that nothing even slows down its use of Apple as a cost-free, outsourced research and development arm.

The way Judge Koh is orchestrating a streamlined and efficient agenda of non-stop legal wrangling that hasn't really accomplished anything over the last three years but permit Samsung to continue the infringment it started in 2010 without obstruction, the first two options seem to be a possible outcome of the second trial.

In one of those scenarios, the jury might find infringement or not in some way, but they would ultimately come to the conclusion that Apple is only owned some inconsequential few millions in damages or perhaps nothing at all. Samsung would then be set free to drop any charade of pretense that it creates anything original in its own products going forward.

This all happened before

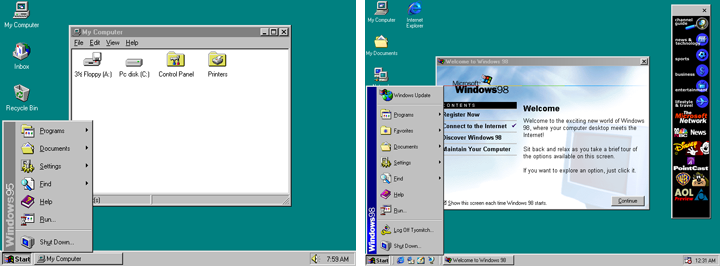

This would be similar to the 1992 decision that, based on a technicality, dismissed Apple's "Look and Feel" case against Microsoft and cleared the way for Microsoft to take everything Apple had created for its own use, for free.

Microsoft subsequently felt so liberated from intellectual property claims that it turned around and also appropriated every element it cared to from Steve Jobs' NeXT Software as well, then signed its own name on the resulting artwork: Windows 95.

The result wasn't just that Apple and NeXT were cheated and that Microsoft was given both credit and cash for having "developed" Windows. That one ruling also set into motion a decade long domination of technology by a company that now had zero respect for other's work, an age of anarchy where Microsoft grabbed everything it wanted and then paid after the fact by offering the attorneys of ruined competitors a few hundred million to settle their claims, after having inhaled all the profits.

Microsoft did this to IBM's OS/2; Lotus SmartSuite; Novell NetWare; WordPerfect; BeOS; Sun Java; AOL's Netscape; and even came back to Apple for a second helping by blatantly stealing QuickTime code in the San Francisco Canyon case. All were efforts by one company to stop competition, kill consumer choice and thwart innovation from challenging its position as the PC profit syphon.

An open world without IP

Microsoft didn't halt innovation via intellectual property claims; it did so by ignoring intellectual property. Samsung today is working to do the very same thing, but the result will be different. Rather than having the world's profits monopolized by a software company, Samsung wants to own everything from chip production to the software platform to finished devices.

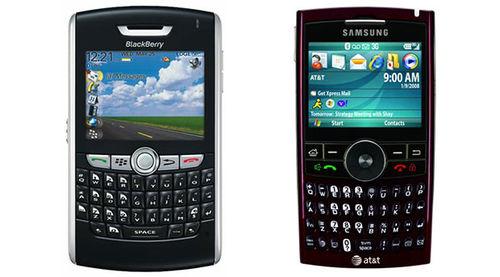

Apple, of course, wants to do the same thing. The difference is that Apple is doing the work to deserve it. Samsung has only ever taken the product ideas of others, which is why it was selling a BlackBerry knockoff unashamedly called the "BlackJack" when Apple unveiled the iPhone and changed the mobile game.

If the court, and in this case, the jury tasked with making a landmark decision, determines that competition is best preserved by rendering patents worthless so that one company can take over through copying rather than building a great original product, the world will be left a place where foreign conglomerates that allow a small number of people to own vast swaths of different industries will compete on a level that American companies (which are prevented from doing the same thing via antitrust laws) can't.

We will live through another Microsoft-like decade of scant innovation apart from predictable speed blips and worthless feature bloat, one where the open source community will achieve its fantasy only to realize that under the rule of a conglomerate, openness will be as valuable as Linux was under the PC industry controlled by Windows.

There will be no capital available to innovators, because there will be no potential payoff for the work they do. It was venture capitalism that kept NeXT a contender long enough for Apple to acquire its technology and build an assault to counter the power of Microsoft in the late 1990s.Even Google has to be hoping that Samsung will lose this case, because if it doesn't, there will be no real market left for the advanced robotics and self driving car intellectual property that it is currently investing its shrinking web ad profits to develop

In a world where patents and technology are worthless, the only hope for defanging a new Microsoft would be the community efforts that banded together to create a series of inconsequential stabs at copying Windows while infighting amongst themselves like Gnome & KDE GNU/Linux did.

Even Google has to be hoping that Samsung will lose this case, because if it doesn't, there will be no real market left for the advanced robotics and self driving car intellectual property that it is currently investing its shrinking web ad profits to develop.

Which choice will the jury make?

Judging from the clarification questions the jury has asked the court so far, it's hard to say what they are thinking. Their questions about Steve Jobs, the involvement of Google, when the patents involved in the cases were selected and the response by Samsung to Apple's claims might suggest that the jury was completely bamboozled by Samsung's scattershot defense of contradictory circles of flawgic.

It's also possible that the irrelevant questions were asked for entertainment value or personal edification, and that the jury actually understands that it is serving in a patent infringement trial, rather than acting as a focus group providing feedback on a possible new Silicon Valley TV drama.

One possible consolation is that this second Apple vs Samsung trial may prove to be nothing more than the short, exposition-heavy sequel that strings together "A New Hope" and a future "Return of the Jedi," and that we'll have to wait another two years for this story to get wrapped up.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

Andrew O'Hara

Andrew O'Hara

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

88 Comments

Such a thoughtful of every possible outcomes, I wish the best for Apple.

Dilger really has no business writing opinion pieces that require subtlety, rather than multiple hammer blows to the subject.

[quote name="SpamSandwich" url="/t/179023/jurys-verdict-in-apple-vs-samsung-case-threatens-far-reaching-consequences#post_2526088"]Dilger really has no business writing opinion pieces that require subtlety, rather than multiple hammer blows to the subject.[/quote] But subtlety is boring; hammer blows make for a much more interesting read. ;)

Dilger really has no business writing opinion pieces that require subtlety, rather than multiple hammer blows to the subject.

Nothing but one man's opinion. If you don't like Daniel's writing, don't read it.

I don't know if I can watch ... I think I will have to hide under the covers till it's all over ... too scary. Great article by the way.