App Store policy and developer fee drama won't change Apple's ways at all

It might be to developers' advantage to complain loudly about Apple and the App Store, but the same system they decry is what gets them to all of their customers — and most devs have been fine with it since 2008.

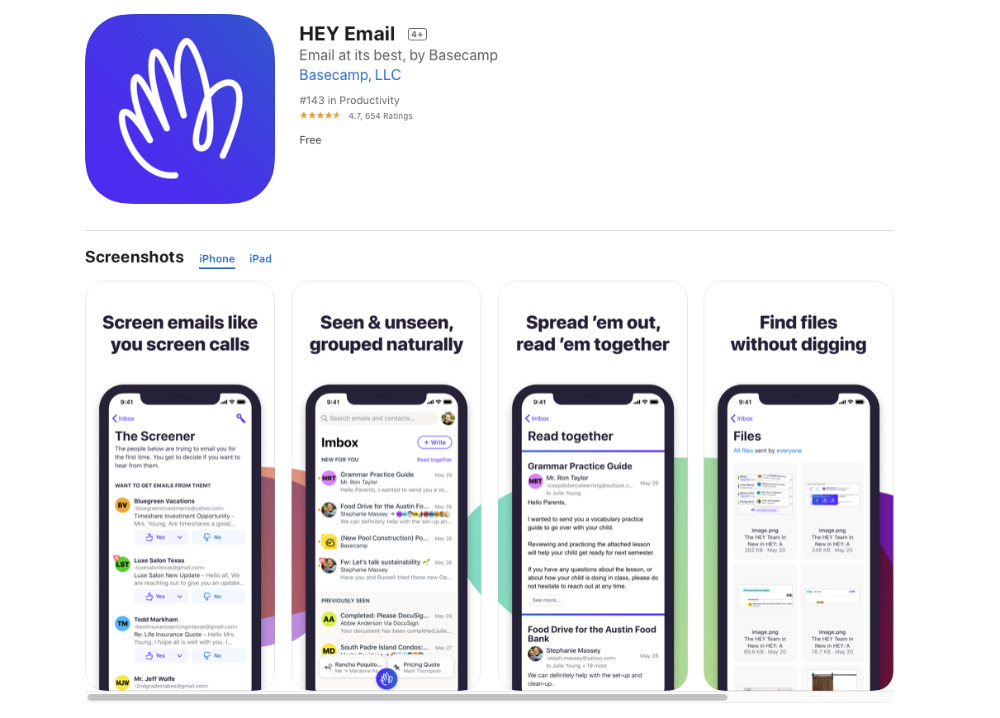

The regular arguments over the App Store, reignited this time around by Hey email developer David Heinemeier Hansson, boil down to a crucial fact. It is very hard to get people to pay for a service if they think it should be free.

That's a problem Apple seems to be facing now, but it's also precisely the same difficulty that Hansson and all developers face over their apps. Hey is an email client and email is free — but he needs you to pay between $99 and $999 per year to use it. We're not here to review Hey, and we can assume that the price is a bargain for some types of email users, less so for others.

Like any other product or service, Hey has to persuade people that they have a problem it can solve, and that it's worth paying for. You can't persuade people of anything, though, if they don't know about it. And then if you do persuade them, you can't profit without a way to get your product into their hands.

His first argument against the App Store on Apple's cut got Hansson and Hey a lot more notice than it might have. But it's the App Store that gets his product to people. It's the App Store that means if he persuades people it's worth it, they can instantly have it on their iOS device.

You'd have to pay good money to have that kind of product distribution, and of course Hansson's argument is that they do have to pay good money. To fire up the argument, and perhaps the publicity machine, he specifically railed against Apple's taking 30% of any subscription fee, though he doesn't also mention that this becomes 15% after the first year.

But, as always, there is more to the story than on the surface, and Twitter blurbs do no justice to the issue as a whole.

Developers welcomed the App Store in 2008

Right at the start, Steve Jobs announced the App Store as a solution for developers. It was Apple's way to get developers to their customers, and vice versa, with the nice advantage that it could sell a few iPhones on the way.

"Most developers don't have those kind of resources," said Steve Jobs. "Even the big developers would have a hard time getting their app in front of every iPhone user. Well, we're going to solve that problem for every developer. Big to small. And the way we're going to do it is what we call the App Store."

Apple makes a staggering amount of money out of the App Store, but it also spends about half of its total take including what it gets from the annual developer fee on the service. It's true that 30% is a lot, but AppleInsider has been told by longstanding developers that they remember what it was like before the App Store.

The world has changed, not least in part because of that App Store, and it is now nearly impossible to get software on CD-ROMs in boxes, much less install the software when you have. Back in these days, the developer might get 30%, but generally less.

Stores would take a cut for putting it on their shelves, for instance, if you could persuade them to stock your software at all. And, they'd take more if they featured it. The box manufacturer, disc presser, and shipping services all got paid.

Of course, back then, software cost a huge amount more than it did now. The App Store has actually devalued apps at least as much as it's promoted them. There are plenty of people who will not pay $0.99 for an app because they believe it should be free.

If your app is selling for $20 then paying Apple $6 is significant, but doesn't feel unreasonable. When you're reduced to scraping by on sales of a buck a time, Apple's $0.30 can feel like the difference between survival and not.

"Because of the market power that Apple has, it is charging exorbitant rents — highway robbery, basically — bullying people to pay 30 percent or denying access to their market," said Rep. David Cicilline. "It's crushing small developers who simply can't survive with those kinds of payments. If there were real competition in this marketplace, this wouldn't happen."

But real competition would mean opening the App Store to other companies, and that would make it closer to the Google Play model. Quite apart from the security issues that riddle Android, Google Play has been running since 2008 and it's assuredly not made as much for developers as Apple has. And it benefits no one if the App Store becomes free.

The way we might feel about Apple's cut, though, doesn't change the fact that you're getting delivered to the entire iPhone and iPad audience with only a $100 annual developer account fee up front. It doesn't change, either, that you have control over whether your app is free or paid for.

What Apple works against is the idea of having an app that comes somewhere in the middle. It's more than fine with Apple if you have an app that is free to download, and that then costs money to keep, or to do more with. It's not fine with them if you're getting money from people who use the app, and Apple isn't.

Whether your audience is directly paying for an app or not, you are profiting from them using it and your service. Apple doesn't complain about the costs it incurs distributing free apps, but it is a cost. So if Apple is paying out and you're raking it in, you're going to have a conversation.

As fair enough as it seems for Apple to get some cash for doing some work, this is how the App Store has gained its biggest friction point for users. Maybe finding an app has become harder and harder, but once you've found it, getting it on your device is so preposterously simple that it has completely erased every other way of buying software.

Unless it's an app where you have sign up or pay up, on a website. Users even have to figure a certain amount of this out for themselves, too, because Apple won't let you put a link in the app to your website to sell a subscription.

This has been a barrier for some time, and Apple isn't going to change it back to allowing it — which is what it was originally. We'd like it to change that policy though, and a few others. That one big change would probably make most of the antitrust problems go away.

Mistakes are not conspiracy

Twelve years on from its launch, the App Store has not changed its systems, has not markedly changed its rules, and it has not altered how much benefit developers get from it. However, a dozen years and millions of apps later, it has inconsistencies.

The current arguments against the App Store try to magnify those inconsistencies and a great many of the disagreements developers have with Apple are valid. But some of them are not, and if it weren't for one major exception, we'd say that the developers of Hey are wrong.

It is odd that Apple should say it was mistaken when it first approved Hey for the iOS App Store, but not because mistakes can't happen. We have personal experience of the App Store approval system allowing an app which it later says shouldn't have been allowed. In our case, we actually thought Apple was right and before we sound saintly and magnanimous, our app had been associated with a project that by then was long completed.

Our attitude aside, the real difference between us and Hey, is that Apple removed our app. They told us they would, they said what we'd need to do to keep it on sale, and we worked the math. It wasn't worth it to us to spend money updating the app, so we let it go, and Apple removed it when they said they would.

We could, and Hey could, skip the App Store entirely and offer solely a web-based app. It's unsatisfactory compared to an app, but it works — and it is even how Steve Jobs believed this should be done in the first place.

Apple points out that the Hey app literally does nothing, if you're not a subscriber. "You download the app and it doesn't work, that's not what we want on the store," says Apple's Phil Schiller.

Hey says that Apple is insisting it add a subscription service via in-app purchase, so that Apple gets a cut. Apple is saying the app does nothing.

If you were adding up the pros and cons of each side, then at this point it'd be pretty even, and hard to say who was right or wrong overall. There is, though, the fact that Apple has done a similar thing before, and perhaps many more times. While saying that apps which are front-ends to existing subscription services, Apple has pressed developers to add in-app purchases.

Amazon, Netfix, and special App Store treatment

Recently, Apple did introduce the ability for Amazon Prime subscribers to rent videos through the iOS app without Amazon paying for it. That looks to the world like Apple giving in and allowing Amazon an exception, but it isn't. Not quite.

"Apple has an established program for premium video subscription providers to offer a variety of consumer benefits," Apple told AppleInsider. "These include integration with the Apple TV app, AirPlay 2 support, Siri support, tvOS apps, universal search, and where applicable, single or zero sign-on."

"On qualifying apps such as Amazon Prime Video, Altice One, and Canal+," it continued, "customers have the option to buy or rent movies and TV shows using the payment method tied to their existing video subscription."

Amazon Prime video gets through because what people are paying for is tied to their separately-bought subscription. You're not making an entirely separate purchase, you are spending more money through your subscription. If you like, that subscription just rose by whatever the cost of your purchase is.

So even if it's a matter of semantics, Amazon Prime is not benefiting from Apple choosing to bend its own rules as people claim it is. That's not the major exception that makes us think Apple has problems.

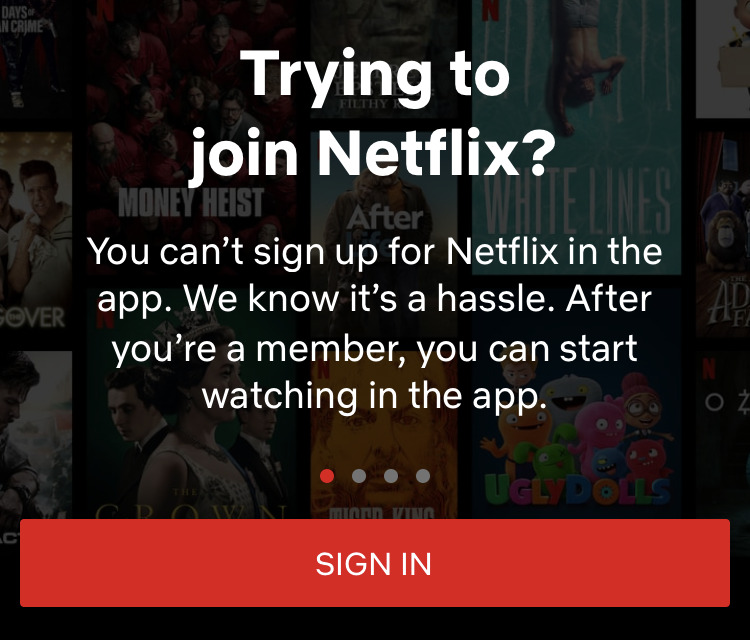

The major exceptions for us are Disney+ and Netflix. Just as with Hey email, both apps do exactly nothing unless you're a subscriber. Both are reader apps but with no option to use it for anything else. Kindle is a reader app but you can open documents in it. Amazon lets you do some browsing and shopping.

Yet Netflix and the Disney+ apps don't do a thing, until you go to the sites and buy a subscription outside of the App Store.

All this said, Apple as a business can make special deals or custom arrangements with who it wants. And, it can refuse to do the same for anybody asking.

Apple and "reader" apps

Also adding to the anti-Apple side is how the App Store inconsistently handles different classes of app, including what it calls reader ones. In theory, it's pretty clear what a developer can and can't do in a reader app.

Apple's developer document says that a user can read content or subscriptions that they've previously bought, but developers can't present an alternative to in-app purchasing. They also can't discourage people from using in-app purchasing if that's available.

So you can't, for instance, buy Kindle books through the iOS app, not without Amazon paying Apple 30%, but you can read the ones you bought there. It's a pain, but at least Apple doesn't block an app that allows you to read purchases made elsewhere.

It's sound and fury, but it signifies something

The pressures against Apple are mounting, internationally. And, the president of Microsoft is actively advocating for App Store antitrust investigations.

"I do believe that the time has come... for a much more focused conversation about the nature of app stores," said Brad Smith, "and whether there is really justification in antitrust law for everything that has been created."

For all that the pressures against Apple are mounting, it's probable that the majority of developers are fine with the App Store. Certainly ones we've talked to who used to ship CD-ROMS are. It's equally certain that developers who have complaints about Apple's procedures have a point.

But it has always and will always come down to the same issue that every product or service has. Whether you're Hey or Apple, you have to get people to become aware of you, then you have to persuade them that you have a problem it's worth paying to solve.

In the App Store's case, the problem it solves is getting apps to every iPhone and iPad user. Every developer has to decide for themselves whether the benefit of that is worth the cost.

That's math, that's economics, that's business. Not wanting to pay for a service does not mean that the service costs too much universally.

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Chip Loder

Chip Loder

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Michael Stroup

Michael Stroup