Hands on, real world use of Apple's latest iPhone 7 models provides overwhelming evidence that the company has a clear vision for the future and is marching toward it without much regard for the opinions of its detractors. This "courage of conviction" backs a series of rather radical and somewhat controversial iPhone 7 changes for Apple— already well known for breaking with the past.

iPhone 7 in Black on top of an iPhone 7 Plus in Jet Black

Too fast, or too slow?

Apple has introduced a variety of features for the new iPhone 7 and iPhone 7 Plus that require some adjustment. There's no analog headphone jack. The familiar Home button loses its mechanical click feel in the shift to a solid state electronic sensor.

Combined with new behavior shifts introduced with iOS 10, how you wake or unlock iPhones— and how it feels when you do— is all changing, and change can be hard.

Just ask the people who never thought their brains would adapt to the reversal in document scrolling introduced in 2011 on macOS X Lion, which made Macs work more like iPads (scrolling down made the document go down; previously, pulling the scroller down was like pulling down a counterweight attached to your document-elevator via a pulley). That issue was once a fierce tempest in a teapot, but you probably haven't devoted much concern to it over the past five years since.

Then too, there's complaints Apple isn't changing fast enough. The new iPhone 7 case is largely the same as previous iPhone 6/6s models, as is its LCD screen technology and the display resolutions of the two models (although the new Wide Color is a very notable advancement). This stands in contrast to Android flagships now touting absurdly high 2K or even 4K resolutions and AMOLED displays like the one used by Apple Watch.

The AppleInsider full review of iPhone 7 will take a closer look at its specifications, in particular examining at how its new A10 Fusion Application Processor performance has increased while the graphically intensive nature of its display resolution stays the same.

Historically, Apple has trounced the performance of high end Androids from Samsung, Google and HTC, not just because it has a faster chip but because iPhones sport fewer pixels on their display.

Samsung in particular has promoted its incredibly high resolution displays without accounting for the fact that their millions of extra pixels mean their weaker CPUs and GPUs are even less capable of matching the performance of iPhones, and without really making the case for those ultra-high resolutions, outside of bragging rights.

Shining a critical eye back at Apple: while its iPhone 7 Home button has changed, it hasn't incorporated any of the micro-touchpad scrolling features or multiple finger recognition gestures that the company has sat on for years since acquiring AuthenTec for use in Touch ID. Given how difficult it is to navigate a 7 Plus sized screen with one hand, why hasn't it loaded up the new Home button with even more functionality?

The iPhone 7 camera makes some big leaps in its ability to take great pictures in low light (and capture Wide Color images). The new dual camera system exclusive to the 7 Plus model is particularly cool. But Apple hasn't done anything to accommodate attaching additional lenses for more versatile or specialty shooting (despite having filed related patents) and hasn't really tried to push the smartphone into point-and-shoot optics territory with a large, real-glass camera lens on the back, the way many of its competitors have tried.

The new A10 Fusion chip establishes Apple as the leader in silicon performance and efficiency in mobile devices, yet the company isn't trying to turn iPhones into a "Mac mini experience" where you can "BYO keyboard and mouse," the way Microsoft has dabbled with Windows Phone "Continuum," nor has Apple tried to bolt on features such as pico projectors or projected keyboard systems or the pill cases and novelty wooden blocks that so enamored David Pierce at Wired when writing about the giddy potential of Google's now scuttled Project Ara.

Clearly, not all innovation is good innovation. So where do you draw the line, and how do you distinguish between expert conviction and silly credulity? Take a look at some of the design decisions Apple has grown famous— and infamous— for making, focusing on what's new in iPhone 7.

Innovation by fire, under fire

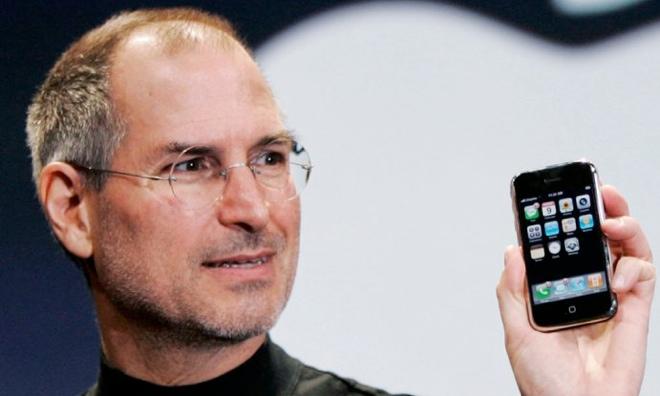

Apple— particularly under its cofounder Steve Jobs— has a long history of aggressively ditching legacy technology while embracing "whats next" and running with it. It effectively killed the floppy, old serial ports and CD-ROMs while stoking popular new mainstream demand for cloud-based storage, USB and digital downloads— none of which it actually invented internally.

Implementing fresh new ideas always sounds great, but it can involve a serious risk of failure if the market isn't ready or if plans otherwise don't work out as expected. Delivering true innovation often requires the long term planning and development of a series of interrelated, enabling technologies. That's expensive and time consuming, adding to the risk of potential failure.

Apple isn't merely a high stakes gambler seeking to be first and regarded by its peers and by journalists as being "innovative." It's often rather conservative, waiting for technologies to mature before introducing its own implementation. Apple wasn't an early pioneer in NFC tap-payments or in wireless home automation but is now a leader in both. Apple wasn't an early pioneer in NFC tap-payments or in wireless home automation but is now a leader in both.

One thing that really distinguishes the company is that it so often makes "decisive decisions" with confident conviction, and despite often being met with vocal (and sometimes over the top) criticism, frequently ends up in hindsight looking to have been right all along.

This isn't because Apple is just "inherently right" or that everything it does is just magical. The company has made mistakes before, and has even issued apologies for the impact of those decisions upon its customers. However, the company's superior batting average in knocking balls out of the park— which appears to be improving over time— can explained by the careful, deliberate timing and execution of its strategies.

Moving too fast— over-promising without being able to deliver— can be just as bad as being left behind in the past by not moving fast enough. Which was worse: Amazon's Fire Phone, which speculatively blew through tons of money and effort to create a novel product nobody wanted, or Nokia's dawdling hesitation to move beyond its tired old Symbian platform?

It really doesn't matter because they both failed.

Why Lightning didn't launch digital audio back in 2012

iPhone 7's much ballyhooed lack of an audio jack raises the obvious question: if not now, when would it happen? But a less obvious question is: why didn't this happen sooner?

Apple could have attempted to wean its users off of analog audio jacks back in 2012 when it first introduced the Lightning adapter on iPhone 5. That very likely would have been too aggressive: the shift to Lightning was already a bit controversial and many wondered at the time if the new reversible, compact jack specification would even catch on.

Many even doubted if iPhone 5 itself would sell successfully, given that Jobs had passed away a full year before its introduction, and Samsung was being broadly hailed as an undefeatable foe by many major news outlets— including Daisuke Wakabayashi of the Wall Street Journal, who didn't admit that "Story Line" was fiction until the end of 2014.

iPhone 5 turned out to be a hit unimpeded by the Lightning shift, and the next year iPhone 5s and iPhone 5c also greatly expanded Apple's global sales and installed base. But scuttlebutt journalists kept bizarrely nagging on the idea that iPhone 5c was a failure for not having outsold Apple's more premium flagship (despite outselling its real competition), and hope still abounded that Samsung was going to beat Apple by leveraging its lead in selling larger phablet devices (albeit with low quality PenTile displays) like the Galaxy Note.

The global tsunami of iPhone 6— which absolutely crushed the unbridled confidence in Samsung and Google's Android platform in general— finally established Apple as a global super power and helped make Lightning ubiquitous.

Today, it's rare to even spot an iPhone or iPad that doesn't use Lightning. Of the installed iOS base now nearing 1 billion devices, only an irrelevant fraction have an old 30 pin Dock connector, and iOS 10 doesn't even bother to support them.

If anything, the shift to Lightning audio cables actually seems overdue in 2016. But it's not just the digital cable jack that's fully ready for a transition away from analog cables. The planets have also aligned for wireless audio distribution that doesn't require any cabling at all.

Apple's pioneering adoption of Bluetooth 4

Back in 2012, Apple had only recently introduced support for the new Bluetooth 4 specification on the previous year's iPhone 4S. A rich ecosystem of wireless Bluetooth 4 (aka BLE) speakers and headphones had not yet developed.

Google's Android and Microsoft's Windows wouldn't adopt modern Bluetooth for years. Google's 2011 distraction with NFC (which it used to power Android Wallet and Android Beam file transfers) meant that Google ignored modern BLE until 2013. Fragmentation and vendor apathy kept BLE from actually working for users even longer (Samsung's S-Beam paired NFC with WiFi Direct, in competition with Google and to the detriment of adopting BLE across Android's largest vendor). Microsoft only added BLE support to Windows Phone 8.1 in 2014.

Everyone may have forgotten, but adoption of Bluetooth 4 and its LE (low energy, also branded as "Smart") and HS (high speed, featuring WiFi integration for throughput) features were driven as uniquely and as powerfully by Apple as the original Intel USB specification was by iMacs back in 1998. This wasn't just an example of Apple flexing its considerable market power; it simply picked the right technology and implemented it earlier, faster and better.

Apple's support for the open Bluetooth 4 standard benefitted its own products above the offerings of Android and Windows Phone makers who suffered from spotty, late adoption of BLE. It also enabled Apple to surprise the market in 2014 with the introduction of Continuity features for iOS 8 and macOS Yosemite.

Google, Microsoft nor their licensees could effectively copy those software features because nobody had a strong installed based of BLE-savvy users, and the NFC connectivity they had focused their efforts on didn't offer a very good substitute for BLE.

In conjunction, Apple did flex its market power with Lightning, a proprietary cabling specification that gave virtually all of its almost one billion installed base of iOS devices sold since a standard, reversible compact port.

Meanwhile, since 2012 rivals such as Samsung have jumped from micro-USB to the bizarrely wide micro-USB 3.0 and back, and only recently have adopted the similarly-reversible USB-Type C port (and Samsung is currently recalling all those Note 7 models due to fire hazard). So Apple has a huge installed base for Lightning while everyone else is barely even getting started with a comparable standard.

Additionally, back in 2012, Apple's own WiFi-based AirPlay audio streaming was also still fairly new on iOS, and huge volumes of Apple TV sales hadn't yet materialized. Apple also had only just started transitioning the Mac's AirDrop file transfer feature to use BLE, making it possible to trade files between modern Macs and iOS devices wirelessly.

Today, mature BLE support powers all wireless transfers and streaming on Apple's platforms. It's not in some early-adopter beta phase; it's been refined for half a decade now. That seems like good timing to begin a transition to wireless and/or Lighting digital audio.

Apple's Beats, silicon feats and headphone jack leaks

Back in 2012, Apple also hadn't yet bought Beats, and lacked the expertise and brand savvy it now has in developing and marketing wireless headphones and speakers to a diverse array of demographics. In addition to building products, you also have to be able to sell them.

Just ask Amazon Fire, HP, Dell, Google's Motorola and Microsoft's Windows Phone partners. Apple had to learn how to sell premium headphones to seamlessly pull off a wireless transition, and it has. It's now neck and neck with the world's leading wireless headphone vendor.

Further, the underlying technologies used in the new AirPods wasn't ready yet in 2012. Apple also hadn't yet blown everyone's minds in the silicon fab industry with its unique A6, or with the surprise debut of its 64-bit A7 that established Apple's serious chip design credibility.

Since then, Apple has launched M-series coprocessors and ever increasingly powerful custom A-series Application Processors that are now rivaling the low end of Intel's desktop computer CPUs. It's not hard to believe that Apple's new W1 chip powering AirPods is a legitimate advance today. It might have been in 2012.Way back in 2012 Apple knew when it introduced Lightning that both digital audio and water resistant electronics were coming

Lastly, in 2012 Apple also lacked experience in building waterproof electronics. Apple Watch, the company's first safely submersible computer, wasn't launched until early 2015, and last fall's iPhone 6s made no promises about its water resistance.

Today, the company's IP67 water resistance for iPhone 7 serves as a significant feature offsetting the lack of a headphone jack, and users understand that losing the old thing is related to gaining that new thing, softening the pain of transition.

At the same time, way back in 2012 Apple knew when it introduced Lightning that both digital audio and water resistant electronics were coming. It expressly designed support for both into the new plug specification, four years before it took the big leap of announcing an iP67 iPhone 7 bundled with Lightning-based headphones. That's evidence of some very advanced planning.

A Home button from the creators of the one button mouse

On iPhone 7, the new Home button design drops its physical button mechanics to become a solid state sensor. It feels different, slightly synthetic. The lower the intensity you set for Home button haptic feedback in Settings, the less different it feels (simply because you're feeling less of it).

Using the new Home button feels a bit like wearing an Apple Watch: both futuristic and a little bewildering, like you're suddenly the age of your parents and technology is now working against you rather than for you.

Do i press the Digital Crown once to get to the screen I want? No, looks like I'll need to press it again. Hmm that activated Siri. Ok let's press it again to see what happens. Ok now there's the watch face I want.

iPhone 7 isn't quite as disorientingly new as Apple Watch (admittedly, watchOS 3 is greatly improving upon the user navigation experience), but the new design of the Home button, combined with the new "push to unlock" behavior of iOS 10, will take some time to get used to.

Just as with Lightning Audio, reaching the current Home button design required lots of developments in parallel. Everyone may have forgotten, but the original iPhone's Home button was an incredible simplification of how software would work on a computer. Everyone may have forgotten, but the original iPhone's Home button was an incredible simplification of how software would work on a computer.

Rather than quitting an app and then being asked about what documents you'd like to save, and waiting around as the app finished up various tasks it wanted to complete before giving you control over your own computer again, the original iPhone introduced a radical new user-first model featuring the equivalent of the similarly round "Go Home" control from the Gong Show.

When users hit the Home button, iOS yanked the rug out from under the current app and took the user to a familiar place to start something new. Developers were given guidelines for how to wrap up their act immediately, rather than being given the opportunity to ignore what the user wanted to do.

That was a sea change from the experience of Windows products, which wouldn't even power down without a lengthy display of "shutting down" that made users feel like they were in line at the DMV waiting to be recognized by a clerk who was busy on an amusing personal phone call.

It's also useful to contrast how Google's Android approached this issue: while it basically copied Apple's software approach, Google replaced the iOS Home button with a shifting interface of real and virtual buttons that kept changing every year, starting with an LED trackball that could light up in various colors. After nearly a decade of wild experimentation, Samsung's latest flagship has settled on a copy of what Apple introduced ten generations ago.

Apple's brutally simple Home button has expanded to do new tasks, such as double clicking to switch between apps or triple clicking to invoke various accessibility features. In 2012 the company acquired AuthenTec and incorporated its advanced fingerprint sensor into the Home button itself, making it super easy to authenticate as part of the login process. This shifted the number of people using a secure passcode from a minority (because it was so cumbersome) to almost everyone (because, why not?).

As a side effect of Touch ID, Apple could introduce Activation Lock (which law enforcement has applauded for achieving a significant decrease in smartphone thefts) and encryption by default (which law enforcement has railed against for impeding their ability to surveil suspects) as well as Apple Pay— which could never have been introduced without first securing and encrypting everyone's iPhones.

When Apple introduced the 5.5 inch iPhone 6 Plus, a Home button double-touch (without depressing) now invoked Reachability. However, despite all the layers of technology and user interface gestures that have been added to the Home button, it still remains a bit like the one button mouse Apple was chastised for retaining in the 90s in an attempt to keep the user interface simple and accessible.

The existing Home button could function like a trackpad, if Apple enabled it to. It's an optical scanner, and your fingerprint is ideal for communicating finger movements in real time. The only reason I can see for Apple to not support this is that it hasn't yet implemented the Focus UI in iOS that it built into Apple TV's tvOS.

And currently, the most valuable touchpad features are already supported by the display; hard press on the keyboard and you can invoke a precise character cursor when editing text. iOS 10 now lets you draw doodles in iMessage (although you have to turn to the wide orientation to begin one). The best application of a Home based trackpad might be scrolling through a document one-handily, but that's already possible to do with flicks, and probably faster.

So while AuthenTec was promoting joystick-like turbo-scrolling and trackpad controls on its fingerprint sensors well before Apple acquired the company, there are plausible reasons why Apple still hasn't exposed that technology. One might be related to how well it works across millions of different people (I haven't actually tried using it, so I can't comment on how well it worked in practice).

Another factor might be related to conflicting plans for the future of the Home button. In the same way that Apple had a clear trajectory in mind when it introduced Lightning back in 2012, there are certainly reasons why it may avoid introducing a minor (and somewhat duplicative) feature on the Home button today. Who knows how long the Home button will even stick around?

That's another factor in "right timing" the introduction of new features.

Apple Pencil on iPhone?

Checkbox pundits like to talk about complex packages of features as if they are all identical nickels in a bucket, where only the total quantity matters. This lacks acknowledgment of the expense and effort required to deliver a given feature.

It also ignores the opportunity costs involved: the value of investing more effort in features that are truly valuable, while deprecating or ignoring ones that may be "cherished" but which are simply braindead impediments to progress, such as Adobe Flash on iPad.

One example: I recently saw some columnist idly suggest that iPhone 7 "should have" gotten support for Apple Pencil, not because it would be really a valuable addition on a mobile phone, but simply to achieve "feature parity" across Apple's offerings.

That's insane if you consider the engineering efforts that would be required to add a pressure sensitive layer to the much smaller screens of iPhones. Would it be limited to iPhone 7 Plus, or would the SE also need the ability to be written on with a precise drawing instrument that's physically longer than any iPhone Apple makes?

Who would use this? And more importantly, would the majority that didn't ever use it want to pay a premium in device thickness, complexity, battery drain and component expense just so a few reviewers could try it out once and pass judgement on how well it works?

Further, adding Apple Pencil support to iPhones would effectively erase a major differentiation offered by iPad Pro models. Based on reviews, an artist who picks up an iPad Pro to use Apple Pencil will generally be happy with their experience.

Imagine that same person trying to be productive testing out Apple Pencil on the small canvas of an iPhone. Even if Apple could make it work, such a feature would likely deliver a compromised experience that left early adopters turned off to the entire idea of using a precise electronic drawing tool.

Samsung sells its Note phablet line with a Wacom-style stylus, and some users like it enough to pay a premium for that model. However, despite being the leading Android pen-driven phablet, the fact that Samsung only sold 2.5 million of them globally in its launch month (as exposed by the recall) shows that it remains a niche device even in its sixth generation, even despite an initial campaign delivering enthusiastic reviews. Back in 2008, Apple was selling 1 million iPhone 3G models in its first weekend.

Apple sells vastly more Plus-sized iPhone models every year than Samsung sells Notes. Apple also has a viable iPad business that sells more tablets than Samsung, and actually makes money on tablet sales. That suggests Apple's engineering decisions related to its drawing tools are just as superior as its engineering work on Application Processors or its pairing of processors to an appropriate screen resolution.

Building bridges rather than burning them builds confidence

There are other important factors that bolster Apple's convictions when making bold or decisive transitions. One is effectively communicating to customers why a shift is worthwhile. A related factor is investing in efforts to smoothly bridge the transition.

When Apple moved its users from Classic Mac OS 9 to the new NeXT-based OS X starting in 2001, it spent years developing and maintaining the Blue Box, a temporary bridge, and Carbon, another legacy viaduct it had to erect and maintain for over a decade before it could divert developers' apps to its preferred Cocoa superhighway API.

Similarly, when the company migrated its Mac users from PowerPC to Intel, it developed Rosetta emulation so old apps could work on the new Macs. Conversely, when it introduced ARM-powered mobile devices, it clearly distinguished between iOS and Macs, erasing any expectation that iPads would be capable of running existing Mac software and making it clear that wouldn't even be a good idea. Instead, apps can be customized for an experience that works best on each platform.

Compare how Microsoft introduced its new ARM-based "Windows" Surface RT with no backwards compatibly with Windows apps. Users had a clear expectation that ARM-based Windows tablets would actually be "Windows" computers because of Microsoft's efforts to brand them all as being the same. The inability of Surface RT to run actual Windows apps was a key issue in its failure as a product.

Similarly, Microsoft's Windows Mobile and Windows Phone conveyed an illusion of compatibility when none really existed, leaving customers unclear on why they'd buy into a new platform that lacked the only reason to buy Windows in the first place: legacy support for Win32 apps. It was only after Windows Phone completely sank that Microsoft decided to build a bridge to it with Universal Windows 10 Platform apps, and by then, nobody wanted to go there anyway.

That's incredibly bad strategy given that Microsoft's greatest legacy has always been legacy.

iPhone 7 and a courage of conviction

The engineering decisions that resulted in the design of iPhone 7 and iPhone 7 Plus involve both aggressively ditching the past to move into the future and also remaining cognizant of the attainable. Or more accurately: knowing what premium package of features will attract sufficient demand to sell iPhones both profitably and efficiency by leveraging massive economies of scale.

Virtually everyone rolled their eyes in unison when Phil Schiller noted that iPhone 7 would drop its legacy headphone mini port in an expression of "courage." That word is generally reserved for valiant war heroes, self sacrificing emergency first responders or individuals like Rosa Parks, who risked ridicule or even violence for standing up against a wall of oppression and hatred.

Getting rid of a jack that is likely to upset some people isn't really on that same level. But Apple wasn't saying that it was. Schiller's comment was a callback to a phrase Jobs had used in explaining why Apple wouldn't be supporting Adobe Flash on iOS. It wasn't "heroic courage," but rather a determined conviction, based on all the evidence available, that it should instead be focusing its efforts on more important work.

The "courage" was a determination to overcome any lingering fears of being wrong; a confidence that its decisions are correct based on all available information and a deep understanding of the needs of users, combined with efforts to soften the impact of transition.

Everyone in the tech industry— including Apple— has been wrong before, having released flop products that were delivered too early, too late, too expensive or not good enough to compete. The difference between Apple and virtually all of its competitors is that it seems to do a very good job of learning from its mistakes, and then translating that learning into advanced, methodical planning that increasingly results in blockbuster successes.

It looks like iPhone 7 has expertly balanced the future with the attainable. What remains to be seen is whether Apple can build enough, fast enough, to capitalize on the demand it has stoked— occurring just as its primary rival deals with explosive failure.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content

125 Comments

After my first weekend with the iPhone 7, the new home button feels natural. I don't think it will be that big of a deal to most consumers.

You didn't mention charging while listening. That's the biggest drawback to using Lightning headphones. Or wireless ones which need to be charged. You give up the functionality of listening on long trips, in a car, plane, train, etc. That's a step back. At least without third party dongles. Apple should have introduced wireless charging first, so you could listen while staying charged.

Rustle? Really? Don't you mean "ruffle"? :D